THE ROSENBERGS DIDN'T TRADE ATOMIC SECRETS

Trump's sinister guru Roy Cohn framed Ethel and Julius Rosenberg

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were executed against a backdrop of world-wide agitation unequaled since the Sacco-Vanzetti case of the 1920's. Fired by Communist propaganda, the demonstrations reached such fever pitch in Paris that a shooting broke out and one man was wounded. The White House in Washington was virtually besieged. The Rosenbergs were the first American civilians to die for spying. They were accused of sending a rough sketch of the atomic bomb to Russia.

— United Press, June 20, 1953

Ethel Greenglass Rosenberg graduated from Seward High School on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and became a secretary in a shipping company. She was a committed Communist and had become a labor activist.

Ethel met Julius Rosenberg at the Young Communist League, they married in 1939, and had two sons, Michael and Robert.

Julius had a degree in electrical engineering from CCNY and ran a very productive spy ring, which passed thousands of classified documents to the Soviets, including bleeding edge U.S. military developments in guided missiles and jet engines. The U.S. Army VENONA project, decrypts of Soviet intelligence traffic, found numerous references to Julius’s spying. One of his codenames was LIBERAL.

Ethel was mentioned in the Soviet spy traffic, but as “Ethel.” She had no official codename, indicating she likely had no formal espionage role.

In the summer of 1950, husband and wife were both arrested. They were not charged with treason, nor espionage, but the vague offense of conspiracy to commit espionage. This placed a lesser burden of proof on the prosecution because conviction did not require tangible evidence that the Rosenbergs had stolen anything or given it to anybody.

When all of the VENONA intercepts and grand jury testimony was finally declassified and released, which took until 2015, this was the extent of the case for the prosecution in PEOPLE v. ROSENBERGS — information known to all the relevant parties in the summer of 1950:

Julius Rosenberg had engaged in non-atomic espionage for the Soviets.

Neither of the Rosenbergs was a member of an atomic spy ring, nor had either of them passed along any secrets related to the atomic bomb.

Ethel Rosenberg was not an espionage agent.

Their execution was a travesty of justice, and Roy Cohn deserves a large share of the blame for their deaths.

J. Edgar Hoover also shares in that ignominy. Because, in 1950, this shameless and relentless self-promoter decided to get greedy.

Hoover had good reason to believe that the U.S. Justice Department could win a conviction against Julius Rosenberg. He had been given a wonderful road map by the decrypted communications, had access to the testimony of confessed Soviet spies who were already cooperating with the government, and the United States was in the throes of losing its mind over what seemed like out-of-control communist subversion.

Hoover knew that it was likely Ethel had a supporting role in her husband’s spying, but there was no evidence she was an active, certified Soviet agent. But, becoming cognizant of a possible path to bigger headlines and greater glory, Hoover decided to find ways to pressure her.

As Julius came under suspicion, more than half a dozen of his known associates had fled the country. One of them, Morton Sobell, was soon located by the Mexican police, had the crap beat out of him, and was dumped at the border in Laredo, Texas for collection by the FBI. Sobell would also be tried along with the Rosenbergs.

But gambling for the bigger score — that is, a full confession from Julius Rosenberg providing all the juicy details of what had to be a massive web of spies, the smashing of which would be seen as a counterintelligence coup worthy of the boldest headlines — Hoover, along with the Justice Department, looked for a way to squeeze both Ethel and Julius into giving up the names of the rest of their network.

In other words, the U.S. government had decided on an inverse strategy from the British, who only months earlier, in January 1950, had discovered a really big atomic spy in their midst. But in order to limit the humiliation, and quickly eliminate the threat, they had arranged for Klaus Fuchs to be tried, convicted and incarcerated all on the same day!

Hoover had the support of senior players in Washington and New York for threatening a mother with the electric chair.

At a secret session of the Joint Congressional Committee on Atomic Energy, Myles Lane, from the Justice Department, said “the prospect of the death penalty or getting the chair” was about “the only thing you can use against these people.”

Gordon Dean, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, offered:

It looks as though Rosenberg is the kingpin of a very large ring, and if there is any way of breaking him by having the shadow of a death penalty over him, we want to do it.

A miscarriage of justice was paved by this zealotry. During the trial of the Rosenbergs, there would be multiple improper ex parte communications between judge and prosecution, and between the prosecution and the defense, and the justification for sentencing the death penalty was set up by suborning perjury.

As this sleazy squeeze went into action, arrangements were made to keep the couple in jail. Bail for Ethel and Julius was set at a sum they couldn’t raise, a total of $200,00— $100,000 for each. Their sons — ages 7 and 3 — ended up at the Jewish Children’s Home in the Bronx.

Next was finding a so-called hanging judge. Forty-year-old Irving S. Kaufman, who was eyeing an appointment to the Supreme Court, was all but jumping up and down and saying, “Pick me!” In a pre-trial discussion, he confirmed a willingness to impose the death penalty as a lever to break Julius Rosenberg, “if the evidence warrants.”

This is where a coiled, heavy-lidded, snarling, Hobbit-like figure would make his entrance on the Cold War timeline. In 1950, Roy Cohn was a 23-year-old assistant prosecutor for the Southern District of New York who had been assigned to the Rosenberg case.

Cohn had graduated from Columbia Law at age 20, and gained notice in 1949 for helping convict 11 members of the American Communist Party’s politburo — a decidedly anti-Constitutional judgement that suddenly made it criminal to admit being a communist.

Cohn may also have played matchmaker in getting Irving S. Kaufman assigned to the case. The son of a New York State Supreme Court judge, Cohn was precociously introduced to the ways and means of exploiting the city’s invisible but very real Favor Bank — or Cesspool of Corruption. As a high school student, he had already figured out how to fix a parking ticket for a teacher.

The Favor Bank also had various hubs, one of them was the Stork Club, where Cohn became a regular, deftly retailing gossip, hearsay and scandal with Hoover, Walter Winchell, and other key players in the destruction-by-tabloid apparatus.

Cohn would be a key player in the next challenge for Hoover and the Justice Department: fabricating a case against Ethel.

One of the people Julius had recruited into his network was Ethel’s brother and fellow Young Communist David Greenglass, who had found himself a machinist at the Los Alamos Lab, working on the atom bomb’s detonation device. During the trial, under questioning by Cohn, David Greenglass would ultimately testify to passing sketches and other top-secret atomic data in the Rosenberg living room.

That now appears to have been a fiction fed to Greenglass by the FBI and the prosecution, including Cohn. David and his wife Ruth did provide atomic bomb information to a Soviet courier, but not through either Julius or Ethel.

It was Greenglass, after being arrested and interrogated in June of 1950, who fingered Julius as his recruiter. But, at the time, he said clearly his sister Ethel had no involvement in the spying. However, in February 1951, ten days before the start of the trial, Greenglass and his wife Ruth were re-interviewed by the FBI.

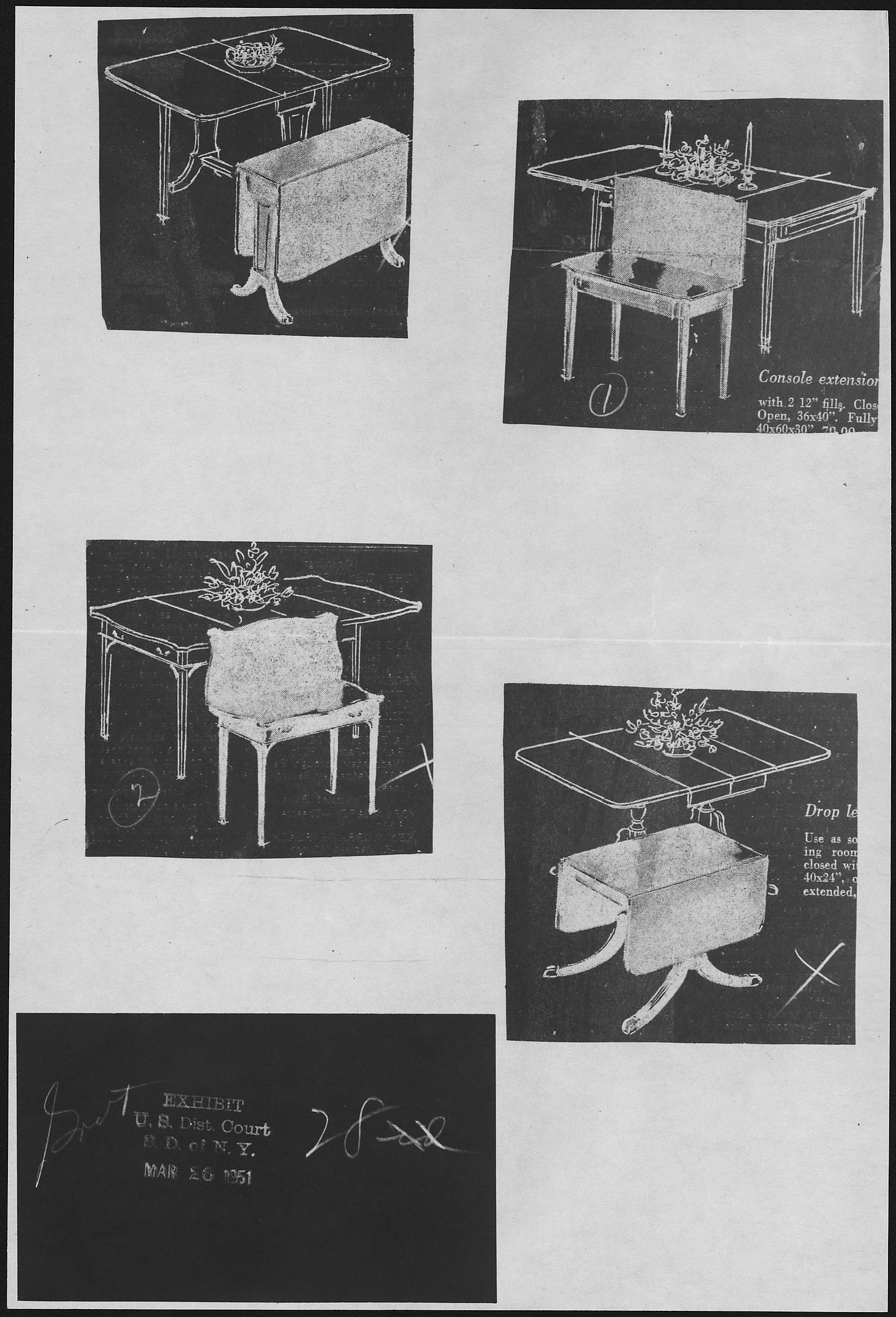

After those interviews, Ethel was suddenly implicated in the conspiracy. The new story was that David Greenglass’s Los Alamos secrets were typed up by Ethel on a folding bridge table in the Rosenberg living room, as witnessed by both David and Ruth.

Like Ethel, Ruth was the mother of two young children, but unlike Ethel, she was demonstrably guilty, enough of a party to her husband’s espionage to be given the codename OSA (“Wasp”) by Soviet intelligence. She was made to understand that if she wasn’t willing to commit perjury, she, too, would be indicted.

The trial began on March 6, 1951, and lasted for three weeks. The only testimony incriminating Ethel was provided by her brother, David, and her sister-in-law, Ruth.

Chief prosecutor Irving H. Saypol told the jurors that when Ethel Rosenberg was at her typewriter, striking the keys, “blow by blow” she was betraying her own country “in the interests of the Soviets.”

The jury took less than a day to reach a guilty verdict.

No one in the FBI hierarchy favored the death penalty for Ethel. Roy Cohn said he did, later claiming he had ex parte phone communications with Irving S. Kaufman urging the judge to give the death sentence to both Ethel and Julius.

Later, Cohn would say of Ethel:

I think she was the stronger of the two. She was the one who got her brother, David, into the Young Communist League to start with. She was the one who kept drilling him full of propaganda until she had him sufficiently hyped up that when it was put to him concerning the stealing and making of those sketches and turning over secret information in the name of the Soviet Union and all of that, he was totally acclimated to what he was supposed to do. Ethel was the strong one, not the weak one, and that is an observation I reached by watching throughout the entire trial, by hearing her testimony on the witness stand, being closer to you than I am to you at this very moment, over a period of many, many days, examining the trial record, the grand jury minutes, and everything else … I never had any doubt about her guilt, but I feel she was the strong one among the two of them and belonged in that case as much as he did, if not more.

This was Cohn’s “communist den mother” theory of why Ethel Rosenberg deserved to die. But from the statement above, and many other statements Roy Cohn made about the case, what you learn for these protestations are that Roy Cohn understood that he was a willing participant in a lynch mob — and uneasy about that fact.

For justification, Cohn would hint at the existence of the VENONA decrypts, which had indeed clearly identified Julius Rosenberg as a traitor — but not Ethel. However, since the VENONA information was never revealed as evidence in any of the trials involving the era’s Soviet spies, Cohn could claim that the VENONA decrypts also incriminated Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny.

By hiding the VENONA details, FBI counterintelligence investigations were constructed backwards. Guilt had been verified. Finding the proof that could be used in court came later. Or proof could be simply fabricated.

Cohn had no qualms with prosecutorial misconduct. He was in the protean stage of contorting and corrupting and abusing the American legal system for his own gain, daring disbarment, becoming a man so lacking in scruples many would judge him to be the most evil person they had ever known.

The young Roy Cohn was ready to let Ethel Rosenberg die because he enjoyed the buzz accrued from being an anti-Communist champion in the age of the Red Menace. He was also a Jewish anti-Semite who saw an opportunity to win favor from an anti-Semitic WASP establishment by appearing to lead the charge against Jews who loved Moscow more than mom and apple pie.

Cohn would later say:

Not all Jews are Communists, but most communists are Jews. I did resent very much the idea of associating Jews with a sympathy toward communism. And I do admit that this is something that has always bothered me, and I’ve tried every way I can to make it clear that the fact that my name is Cohn and the fact of my religion [is perfectly compatible] with my love for America and my dislike for communism.

Judge Irving S. Kaufmann sentenced Martin Sobell to 30 years. For cooperating, David Greenglass received a lesser sentence of 15 years. Ruth Greenglass would never be charged. To be clear: David and Ruth Greenglass had provided atomic bomb secrets to the Soviets.

On April 5, 1951, announcing his reasons for putting Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to death, Kaufmann made one of the most dishonest, ignorant and hyperbolic statements of the entire Cold War:

I consider your crime worse than murder … I believe your conduct in putting into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb, years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb, has already caused, in my opinion, the Communist aggression in Korea, with the resultant casualties exceeding 50,000, and who knows what millions more innocent people may pay the price of your treason. Indeed, by your betrayal, you undoubtedly altered the course of history to the disadvantage of the country.

Kaufman also said:

The evidence indicated quite clearly that Julius Rosenberg was the prime mover in this conspiracy. However, let no mistake be made about the role which his wife, Ethel Rosenberg, played in this conspiracy … She was a full-fledged partner in this crime.

The wife and mother standing before Kaufman had no more than a high school degree and the extent of her guilt had been contrived by the prosecution. Her husband had betrayed his nation, but he did not do so from inside the Manhattan Project, like his brother-in-law, who, as it turned out, was going to live a long life.

David Greenglass was released from prison in 1960, after nine-and-half years. He died in 2014, age 92.

In the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Nobel-Prize winning scientist Jacques Monod wrote of the verdict:

We could not understand that Ethel Rosenberg should have been sentenced to death when the specific acts of which she was accused were only two conversations; and we were unable to accept the death sentence as being justified by the “moral support” she was supposed to have given her husband. In fact the severity of the sentence, even if one provisionally accepted the validity of the Greenglass testimony, appeared out of all measure and reason to such an extent as to cast doubt on the whole affair, and to suggest that nationalistic passions and pressure from an inflamed public opinion, had been strong enough to distort the proper administration of justice.

Even had David Greenglass used Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to pass atomic secrets, he was but a cog in the machine, an Army Sergeant in a relatively low-level position at Los Alamos who likely only told the Soviets what they already knew.

From the British side alone, Joseph Stalin and his physicists had been inundated with a flood of timely and relevant atomic research. The Manhattan Project was an Anglo-American alliance, and the Anglo side — displaying desperately poor counterintelligence — had hired known communists Klaus Fuchs, Allen Nunn May and Bruno Pontecorvo, who were each world-class theoretical physicists and, as such, part of the group of people tasked with actually making the bomb work.

Before the Manhattan Project was even established — on August 13, 1942 — Fuchs was already communicating top secret atomic research to the Soviets, allowing the Kremlin’s atomic czar Igor Kurchatov and his able colleagues to jump start nuclear weapon development.

In addition, Kremlin mole Donald Maclean was perfectly positioned during the war. In a senior diplomatic role for Britain, he’d been conveniently posted to America and provided Moscow with a Pentagon perspective of the bomb’s progress, including a heads up about the Trinity test at Alamogordo.

Fuchs and May would each be jailed for less than 10 years. Pontecorvo and Maclean were able to defect to the USSR before Western justice could intervene.

All of these Soviet spies from Britain were far, far more significant actors in the contours of the Cold War contest than Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

Kaufman had scheduled the executions for the week of May 21, 1951. Appeals took two years. Worldwide protests began.

Marxist and existentialist Jean Paul Sartre said: “Your country is sick with fear … you are afraid of your own bomb.”

In the communist L'Humanité, Pablo Picasso wrote: "The hours count. The minutes count. Do not let this crime against humanity take place."

Pope Pius XII appealed to President Dwight D. Eisenhower to spare the couple.

So did Ethel’s brother David, writing to Eisenhower:

If these two die, I shall live the rest of my life with a very dark shadow on my conscience … Here I had to take the choice of hurting someone dear to me, and I took it deliberately. I could not believe that this would be the outcome. May God in His mercy change that awful sentence.

Answering the global outcry, Eisenhower adopted Kaufman’s judgement and amplified it, saying “by immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war, the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people all over the world.”

Ike told son David, who was serving in Korea, that if Ethel were spared, it would only encourage the Soviets to establish an all-female spy corps.

Meanwhile, Roy Cohn became convinced that the communists were after him. He asked the FBI to check if his phones were tapped and if his office contained hidden microphones. Hoover ignored Cohn’s jitters.

On the morning of the execution, June 19, 1953, J. Edgar Hoover sent six field agents to Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, New York. One was a stenographer capable of transcribing 170 words per minute.

At the prison, the agents turned two cells on death row into offices. The FBI team waited to see if after three years behind bars, and moments before their electrocutions, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg would at last relent and confess.

The following morning, newspapers around the world carried the story of the execution of 35-year-old Julius Rosenberg and his 37-year-old wife Ethel.

This was the lead by the United Press wire service:

SING SING PRISON, N.Y. ⎼ The United States had exacted full payment today from Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for the atomic age betrayal of their country.

Their lips defiantly sealed to the end, the husband and wife spy team went to their death in Sing Sing's electric chair shortly before sundown ushered in the Jewish Sabbath last night.

The Government had hoped to the last that they would talk. Executioner Joseph Francel sent the electrical charges through their bodies.

It took three shocks of 2,000 volts each to electrocute Mr. Rosenberg. Four jolts swept through Mrs. Rosenberg and still she was not dead. A fifth was ordered.

Thus was sealed the secrets of a Soviet spy ring which many experts fear may still be operating in this country. The Rosenbergs refused to the end to trade the secrets for their lives.

In subsequent paragraphs, the story provided minute-by-minute and unsparing detail of the execution procedure, including the multiple shocks needed to kill Mrs. Rosenberg:

Ethel, attired in a dark green figure print dress, came calmly, stoically, into the death chamber only two minutes after her husband's body had been taken into an autopsy room less than 20 feet away.

She was strapped in the chair. The cathode element, soaked in a saline solution and resembling a football helmet, was fitted to her head.

Then Francel, an electrician whose sideline is acting as executioner in prisons in five states, threw the switch. That was at 8:11 1/4.

When the first electric shock was applied, a thick white stream of smoke curled upward from the football-type helmet on her head.

The juice went off and the burned body relaxed.

Then came the second shock ... the third ... the fourth. A prison guard stepped forward, released one strap and pulled down the round-necked dress.

Drs. [H.W.] Kipp and [George] McCracken applied their stethoscopes, then conferred in low tones. Executioner Francel joined them.

“Want another?” he asked.

The doctors nodded and stepped back to their positions beside [Warden Wilfred] Denno, alongside the wall.

Francel again applied the switch.

When the doctors examined the body for a second time, they quickly pronounced her dead.

On June 23, 1959, six years and four days after the Rosenbergs were executed, Klaus Fuchs — then 47-years old — was released from the maximum security Wakefield Prison in West Yorkshire, England. He had served nine years, given one-third off for good behavior. Fuchs immediately emigrated to East Germany, where he would play a critical role in helping the Chinese develop their first nuclear device.

In 2001, David Greenglass told author Sam Roberts that he had lied on the witness stand about his sister’s involvement. Wrote Roberts: “Without that testimony, Ethel Rosenberg might never have been convicted, much less executed.”

In 2003, Greenglass gave an interview to 60 Minutes. He claimed Roy Cohn had pressured him to make up the story about Ethel and the typewriter.

He also said: “I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister. How do you like that?"

Asked why he thought Julius and Ethel maintained their silence to the end, he replied:

"One word: stupidity."