When I learned of the death of Coach Casey Converse from Olympic swimming colleague Mike Unger, I wrote back that it had been “a gift” to know him.

A day later, one of Casey’s fellow coaches and competitors had the same reaction. In a tribute published by Swimming World, Chuck Warner wrote:

Are you a swimmer or coach with an attitude of gratitude? You might take a moment to consider appreciating the incredible gift that the life of Casey Converse has brought to all of us.

I first met Coach Converse in 2014. It was over lunch in the cafeteria of the United States Olympic Committee Training Center. At this particular cafeteria, you can’t avoid the palpable electricity from the energy and intensity being emitted by young Olympic hopefuls of all sports, of all shapes and sizes … all ultimately united by their ravenous appetites, each wielding trays with copious amounts of food that they rapidly inhale before reloading.

I was lunching with Casey because USA Swimming, under Mike and Chuck Wielgus, had hired me to direct a documentary, The Last Gold, which focused on the women’s swimming competition at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, where doped East German athletes dominated the competition. Knowing that Casey was already deep into a book about the same topic, titled Munich to Montreal, USA Swimming had logically asked him to serve as a consultant on the film.

If my view was top down, with a steep learning curve, Casey’s was bottom up, and very personal.

The author of Munich to Montreal had lived the story from every possible perspective: as a swimming prodigy in the early seventies; as an Olympian in Montreal; as a champion competitor; as a distinguished coach who helped to nurture sports equality for women; and as a motivator who had pushed his athletes to find the outer edge of what is possible.

To be clear, Casey’s book, published in 2016, is not a memoir. It is, rather, the result of a burning passion project that the author had felt a moral need to write. Because, above all, Munich to Montreal is a story about galling, unremedied injustice and astonishing, unconditional resolve. And Casey Converse wanted the world to know that this injustice and this resolve should never be forgotten.

Casey’s road to becoming an elite competitor began in his early teens, when he bravely left Alabama for Southern California. This was a “less-connected” America, when extreme culture shock was still possible and a trip from the Deep South to SoCal’s raging hip and cool might as well have been a space voyage between distant stars. At the same time, it was also a world more simply defined by the geography of a Cold War: Capitalist versus Communist, Us versus Them. We were right. They were wrong.

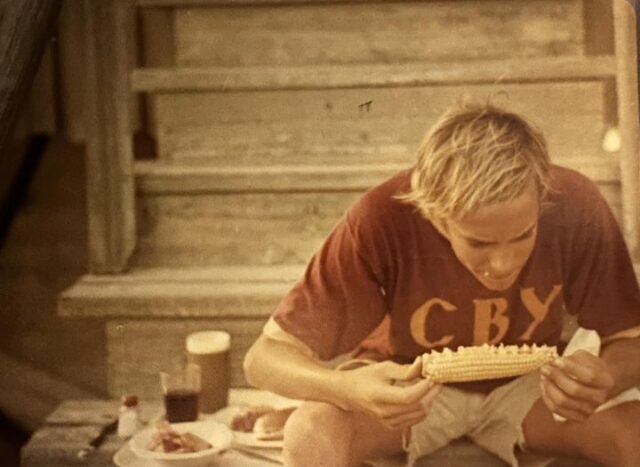

Casey made the journey to California in order to see how far he could stretch his incipient swimming talent. As he arrived at Los Angeles International Airport, he was met by one of the central figures of Munich to Montreal, Mark Schubert, who would eventually become the 8-time U.S. Olympic swim team coach. Schubert, one of a growing legion of transplants from the East, was creating a swim mecca in Mission Viejo. (Below, a family photo of the sun-bleached young swimmer.)

While at Mission Viejo, Casey also swam in the same pool as another central figure of his book, the remarkable and irrepressible Shirley Babashoff.

Babashoff might be the a) greatest Olympic athlete to have b) the most essential and c) least-known legacy. After her superior performance at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, and for that matter the three previous years of tenacious swimming against doped East German athletes, she deserved a spot in the swimming pantheon with Mark Spitz and now Michael Phelps. How her rightful place in history was effectively stolen from her is something you fully learn in Casey’s book — and The Last Gold.

At age 18, a high school senior, Casey joined Shirley Babashoff on the Montreal Olympic team. And his men’s team ─ powered in part by a superlative core from the new collegiate power USC ─ is arguably the greatest Olympic team in any sport in the history of the modern Games. Moreover, Casey’s Olympic coach was Indiana’s Doc Counsilman, the author of the first great training bible for swimmers. In Munich, Counsilman had guided Spitz to seven golds.

Casey was already a four-time U.S. national champion when he returned to Alabama to swim for the Crimson Tide. As a freshman competing at the NCAA Championships, he earned a place in swimming history as the first to ever break 15 minutes in the mile. Such victories are years in the making, calculated in wearying workloads of thousands and thousands of laps, AM and PM, day after day.

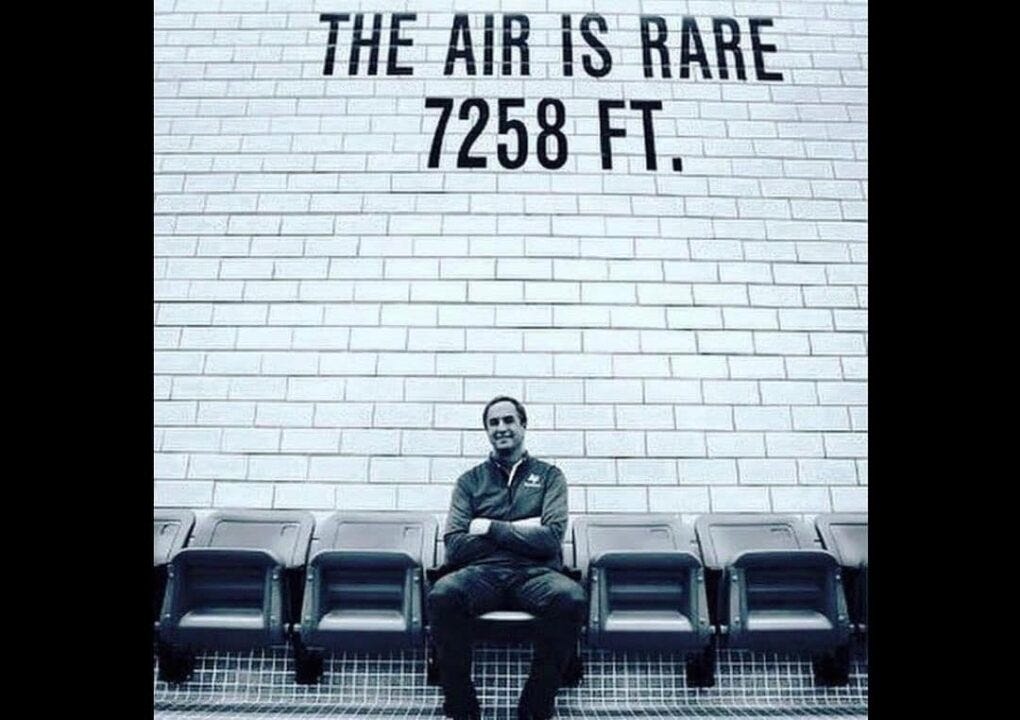

This perpetual student of the sport never ceased his search for excellence, and like many everlasting learners, he became a lifelong teacher. He spent 29 years coaching at the Air Force Academy, on a campus dramatically perched amid the Rockies in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Here, a visitor to the pool is first struck by a sign with large block letters that advertises the lung-searing elevation at which they will be expected to compete. (Below, Casey sitting beneath the warning, in an Air Force Academy photo.)

In 1995 and 1996, the Air Force women’s team won back-to-back Division II NCAA Championships. The 1996 team set the all-time scoring record. And though high altitude may give Air Force athletes a slight home-field advantage, their frightening academic workload is, notably, rather consumptive, science on top of engineering on top of mathematics. Casey was equally proud – if not prouder – of what his cadets did after graduation. In the first Gulf War, one of his swimmers became the first female pilot to be decorated for a combat mission. Another swimmer returned to the Academy as the head of the History Department.

In witnessing the difficult and ongoing evolution of women’s sports in America, Casey gained a deep, emotional understanding of the struggle endured by Babashoff’s pioneering generation of the 1970s, and those who’ve followed. But there was an even greater force impeding the women of the Montreal Olympic team: a win-at-all-costs East German sports machine that was poisoning its young athletes for what would be victory in the short-term but also, for many, horrific, long-term health issues. This was compounded, in the West, by a conspiracy of silence. No one in the swimming establishment was prepared to confront the increasingly obvious: that East Germany was running a very sophisticated doping industrial complex.

Coach Converse was with me and Mike Unger when we rolled our first frames of The Last Gold. This was for a scenic shot of the vineyards surrounding the classically quaint village of Schornsheim, Germany, the home of the star of the 1976 East German team, Kornelia Ender. On that same trip, we’d also visit the former East German town of Bitterfeld, where Ender was born and raised – and from which she departed long ago. For Casey, it was a chance to compare and contrast.

Bitterfeld is hardly a postcard destination: it’s yet another example of the kind of drab, soulless uniformity built by a failed state, which came to determine that gold-medal performances at the Olympics might provide desperately-needed political legitimacy at home and abroad. In this saga, Ender, and her teammates, were victims, too: doped without their knowledge, or their consent. As Casey walked the sidewalks of Bitterfeld, he remembered the bountiful sunshine of his California training days. The process of comparing and contrasting made it even clearer to him just how fortunate he was to have been born in the USA.

While Casey was researching his book, and as I was doing the same as film director, we were able to play detective for each other. Devoted digging was required. Pathological lying was the First Commandment of the East German state. Secrets were ruthlessly maintained. At the same time, the environment for American women’s sports in the 70s was often fuzzy, improvisational, and even invisible.

Though the tragedy of the Montreal Games still lingers, those Olympics also demonstrated a triumph of the will. The 1976 American women’s swim team did not go down without a fight. The title of USA Swimming’s documentary refers to the last race and the “last gold” of the swim competition in Montreal, the 4x100-meter women’s relay, when a clean U.S. team of Kim Peyton, Wendy Boglioli, Jill Sterkel, and Shirley Babashoff narrowly – but incredibly – defeated a doped East German team.

As importantly, many of the central figures of Munich to Montreal and The Last Gold – American and German – were people of enormous character, steadfast and shining; people who spoke truth to power with an extraordinary amount of courage.

I only worked for two years on the production of the film. However, Casey’s book about this Shakespearean cautionary tale had germinated over a lifetime, become a labor of love born out of outrage, and every paragraph possesses the depth of rare knowledge.

The cover of Munich to Montreal and the title frame of The Last Gold are also forever linked. It’s representative of a kind of magic specially created by Casey. The ridiculously ambitious image was recorded at the Air Force Academy pool. To make it happen, a truck of film gear had to be cleared and unloaded at this high-security campus — not a simple ask. There was another truck containing crates of equipment for the divers doing the underwater photography. We had the generous cooperation of the Air Force’s women’s swim team, who wore the uniforms used at the 1976 Montreal Games. Large U.S. and East German flags had to be suspended above the water.

The surreal silhouette image produced during that shoot was as perfect as we could have imagined. And it could only have been made possible by the sunny conviviality, can-do spirit, and insouciant inspirational aura of a man many of us were gifted to know.

This is a beautiful sensitive reflection on the life of an honorable man.