After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 16 of 12, or more!)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: Jimmy Byrnes left his White House job, as Director of War Mobilization, after the April 12, 1945 death of Franklin Roosevelt. He soon returned to his native South Carolina and, it appeared, had left public life, at least temporarily. In truth, Byrnes had become even more powerful, as Truman’s most important advisor – but acting in the shadows, without an official title. The week after FDR’s death, from April 13 to 17, 1945, he was in Washington, at Truman’s side. On May 2, 1945, Truman made Byrnes his surrogate on the secret Interim Committee, created to establish if and how the atom bomb would be used. Meetings of that body had Byrnes returning to Washington throughout the month of May. Byrnes wouldn’t “officially” join the Truman Administration until being named Secretary of State, on July 3, 1945. But prior to that date, he was helping to run the country and, in that role, was the leading proponent for the use of the atom bomb.]

Q: This series seems headed to the judgement that it wasn’t necessary to use atomic bombs in World War II. Is that correct?

A: Yes.

Q: Who are you to say the bomb wasn’t necessary?

A: Fair question. So let’s go to the experts. Here’s World War II historian Ian Toll: “In 1945, eight Americans (four generals, four admirals) held five-star rank. Seven later stated that the bombings were either unnecessary to end the war, morally indefensible, or both.” Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, made his objections to dropping the bomb known to the Secretary of War before the atomic attacks on Japan. Eisenhower later said, “It wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.”

Q: Wait a minute. Wasn’t there a simple choice – either drop the bombs or let a million American soldiers die in an invasion of Japan?

A: As nuclear expert Alex Wellerstein explained, that was a “false dichotomy … started explicitly as a propaganda effort by the people who made the bomb and wanted to justify it against mounting criticism.”

Q: When did Harry Truman first get a full picture about the making of the bomb?

A: As previously noted in part 14 of the series, Truman’s role as head of the Senate’s oversight committee on U.S. defense spending made him aware that a fearsome new secret weapon was being built. But on April 13, 1945, the day after Roosevelt’s death, Jimmy Byrnes and Secretary of War Henry Stimson provided the new President with all the relevant details about the bomb.

Q: What was Truman told in that meeting?

A: Byrnes and Stimson told Truman that the device would soon be tested in the barrens of New Mexico. “This,” wrote Richard Rhodes, “is when Byrnes crowed that the new bombs might allow the United States to dictate its own terms at the end of the war.” On the other hand, Secretary of War Stimson, as Truman wrote, “seemed at least as much concerned with the role of the atomic bomb in the shaping of history.” (Below, center and wearing fedora, Henry Stimson, speaking with Jimmy Byrnes, on the far right):

Q: Was Truman concerned with the role of the atomic bomb in shaping history?

A: No. He was far more interested in how it could end the war on America’s terms – the advice coming from “co-President” Jimmy Byrnes. “Minimally,” wrote Gar Alperovitz, “[Byrnes] seems to have seen [the bomb] from the very beginning as leverage to help American diplomacy and, more likely, as the critical factor, which – if shrewdly handled – would allow the United States to impose its own terms once its power was demonstrated.” As Martin Sherwin wrote, “The nuclear option was preferred because it promised dividends.”

Q: How was the atomic bomb going to end the war on America’s terms?

A: Byrnes envisioned the bomb accomplishing three goals.

Q: Goal number 1?

A: The shock of the atom bomb could be used to compel Japan into accepting an unconditional surrender – solidifying domestic political support for the new Truman Administration. Only 12 percent of Americans disapproved of the demand for an unconditional surrender; polls also showed that a third of all Americans wanted Emperor Hirohito executed.

Q: Goal number 2?

A: The bomb also had the potential of ending the war before the Soviets joined the fight in the Pacific – ensuring that Soviet influence wouldn’t expand in Asia and, in particular, preventing any chance of the U.S. being forced to share post-war Japan with Stalin. (At Yalta, Stalin had secretly agreed to end the Soviet neutrality pact with Japan and join the war in the Pacific “two to three months” after Hitler had been defeated. This news was greatly welcomed by the U.S. military chiefs, who told Truman that Soviet participation, even if not essential to victory, would likely hasten Japan’s surrender, thereby saving American lives.)

Q: Goal number 3?

A: Once unveiled, this new secret weapon would dramatically shift the balance of power in America’s favor and therefore threaten Stalin, ideally enough to temper his rapaciousness in Eastern Europe — and everywhere else. (For many U.S. military and political figures, Soviet communism was feared as much as, if not more than, German Nazism.) This third goal for using the bomb was particularly important to Byrnes.

Q: Why was this third goal particularly important to Byrnes?

A: A more conciliatory Stalin might improve the South Carolinian’s public standing. After FDR’s death, angry Polish-Americans had only Byrnes to blame for, in their view, “handing” Poland to Stalin at the Yalta Summit. (FDR had made Byrnes the chief spokesperson for the summit’s “achievements,” which proved to be overstated, as the author explained in part 14 of the series.)

Q: Did Truman and Byrnes achieve any of these goals?

A: No. The U.S., after the using the atom bomb, still settled for a conditional surrender with Japan — allowing the Emperor to stay. The use of the bomb did not prevent the Soviets from entering the war against Japan. In fact, it was the entrance of the Soviets into the Pacific theater, on August 9, 1945 — after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic attacks — that acted as the jolt inducing Japan’s prompt capitulation. Finally, Stalin’s imperial ambitions were not restrained by America’s atomic monopoly. The Soviets not only established a puppet state in Poland, but did so in East Germany, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Romania. Stalin wasn’t greatly deterred by America’s atomic monopoly because he knew it was going to be temporary. The Soviets had a bomb by 1949.

Q: What are the lessons from this failure to achieve those goals?

A: Truman should have paid more attention to Secretary of War Henry Stimson when Stimson told him to consider how the atomic bomb would shape history.

Q: Can we get back to the plans for the invasion of the Japanese mainland?

A: Sure.

Q: When Truman assumed the Presidency, in April 1945, what was he told about an invasion of the Japanese mainland?

A: The U.S. had formulated detailed plans for a November invasion of Japan’s southernmost main island, Kyushu (Operation Olympic). The staff for Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief of U.S. Forces in the Pacific, estimated that 50,000 American soldiers would be killed or wounded in the first month of a Kyushu invasion, and, after three months, there would likely be at least 100,000 casualties — to be clear, that’s dead and wounded. There was never any U.S. military estimate that one million troops would be killed as a result of invading the Japanese mainland. (Fyi, in the entirety of World War 2, in Europe and the Pacific, the number of U.S. soldiers killed was 420,00.) Plus, there’s this: When the April 1945 invasion plans were made, the top U.S. commanders in the Pacific were already confident that the Japanese would surrender by September or October 1945, even without the atom bomb. (Below plan for Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyushu):

Q: Why were the top U.S. commanders confident in April 1945 that the Japanese would surrender by September or October 1945.

A: As noted in part 15 of this series, Air Force general Curtis LeMay had estimated that his bombers would likely run out of Japanese targets to destroy by September-ish 1945 — two months before the scheduled invasion. In fact, as Richard Rhodes noted, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki survived to be atomic-bombed only because Washington had removed them from Curtis LeMay’s target list.” According to Air Force Brigadier General Roscoe C. Wilson, “LeMay felt, as did the Navy, that an invasion of Japan wasn’t necessary. He saw that we had the Japanese licked. His planes were encountering little or no air opposition because the Japanese fighters were out of fuel. Without the bomb, LeMay could have destroyed all the Japanese cities anyway.” Moreover, in April 1945, the Japanese were asking the Soviets to mediate a surrender.

Q: Did Truman know the Japanese were asking the Soviets to mediate a surrender?

A: Yes, because U.S. codebreakers were able to intercept top-secret Japanese diplomatic messages. Robert J.C. Butow would write, “The mere fact that the Japanese had approached the Soviet Union with a request for mediation should have suggested the possibility that Japan, for all her talk about ‘death to the last man,’ might accept the Allied demand for unconditional surrender if only it were couched in more specific terms than those which Washington was already using to define its meaning.”

Q: What “specific terms” were the Japanese seeking?

A: They wanted to protect their Emperor.

Q: Why was protecting the emperor so important?

A: For the Japanese, Emperor Hirohito was seen as a god and they wanted to prevent him from being humiliated or even executed. Even before the Nazis surrendered, on May 8, 1945, a trial for German war crimes was being planned. The Japanese envisioned their Emperor being convicted as a war criminal and ignominiously hung from the end of a rope. “The Japanese were already on their last legs,” said British Major General Sir Hastings Ismay, “but if they were given to think that a rigid interpretation would be placed on the term unconditional surrender and that their Emperor – to them the Son of Heaven – would be treated as a war criminal, every man, woman and child would fight on till Doomsday. If, on the other hand, the terms of surrender were phrased as in such a way to appear to preserve the rights of their Emperor to order them to lay down their arms, they would do so without a moment’s hesitation.” (Below, from April 1945, U.S. War Department illustration of Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito):

Q: Was Truman aware that letting the Japanese keep their Emperor might induce a surrender?

A: Yes. In addition, Truman was repeatedly told to reconsider his insistence on a strict definition of unconditional surrender. As Tsuyoshi Hasegawa wrote, “many influential advisers, such as Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Under Secretary of State Joseph Grew, and Navy Secretary James Forrestal, came to advocate revision of the surrender conditions in such a way as to allow the Japanese to maintain the monarchical system under the present dynasty. This concession, they argued, would strengthen moderate elements that surrounded the emperor and induce them to seek early surrender.”

Q: Why didn’t Truman listen to his influential advisers about modifying the terms of surrender?

A: Because Jimmy Byrnes repeatedly expressed his opposition to the idea of keeping the Emperor — a “conditional” surrender — and it appeared that Truman trusted Byrnes more than anyone else.

Q: Might it have been possible to end the war against Japan sooner than August 1945?

A: Yes. After the Germans surrendered, U.S., Soviet, and Japanese officials paid closer attention to their endgames in the Pacific. The defeat of the Third Reich created immediate new perils for the Japanese: the ferocious American war machine was no longer split between two theaters of war, and the Red Army was freed up to join the fight in the Pacific. According to Herbert Feis, fighting could have ended before July “if the American and Soviet governments together had let it be known that unless Japan laid down its arms at once, the Soviet Union was going to enter the war. That, along with a promise to spare the Emperor, might well have made an earlier bid for surrender effective.”

Q: Was there any chance of that happening?

A: Hard to imagine, given the nature of who was in charge of the three countries in question. Japan’s leadership wasn’t going to surrender without an assurance that their Emperor was protected and no assurance was forthcoming. With the soon-to-be-delivered atomic bomb, a weapon out of science fiction, Truman and Byrnes thought they had the means to force Japan into an unconditional surrender (wildly popular with U.S. voters) before the Soviets could enter the Pacific War (and possibly occupy Japan). Stalin wasn’t interested in making peace with Japan until the Soviets had regained the sizeable amount of Far East territory that had been lost in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05. He also wanted a piece of the Japanese mainland and even a split occupation with the U.S., like was being done with Germany.

Q: So all three parties were prepared to let the killing continue?

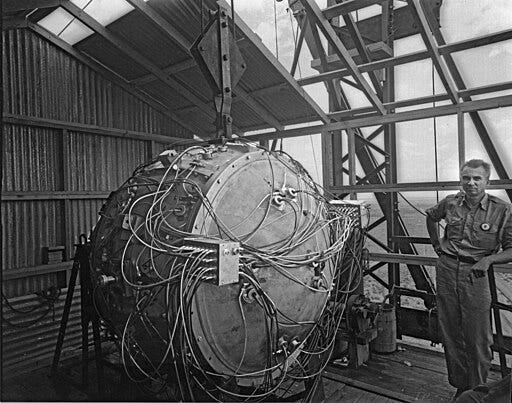

A: Essentially. The Japanese thought they might be able to work out acceptable terms of surrender with Stalin. That was a fantasy — Stalin wasn’t interested in making peace. But what he did do was pretend to listen to Japanese peace overtures. The purpose of the delay tactic was to give the Soviets more time to move approximately 1.5. million troops across the Asian continent, from the European theater to a new Pacific theater. His invasion plan would be foiled only if the war ended too soon. As for Truman and Byrnes, they were ready to wait for the atom bomb to be tested. But it was certainly questionable to be putting so many eggs in the “atomic bomb basket.” It was hardly a sure thing that this incredibly complex new device would produce the promised big bang. (Below, the first-ever atomic explosive device, known as “The Gadget,” during assembly for July 1945 test in New Mexico):

Q: Was there pressure placed on Robert Oppenheimer and the Los Alamos Lab to get the bomb completed?

A: Yes. Said Oppenheimer, “I don’t think there was a time where we worked harder at the speedup than in the period after the German surrender and [before] the actual combat use of the bomb.” For Truman and Byrnes, every day the bomb wasn’t ready gave Stalin more time to move the necessary forces to the Far East and begin his attack on Japan.

Q: Did Oppenheimer ever express any qualms about using the bomb?

A: Not during the war.

Q: Did anyone of significance inside the Truman White House ever express any serious misgivings about using the atomic bomb?

A: No. Nor was there much of a chance for dissent to percolate. The Interim Committee — a civilian group created on May 2, 1945 to advise the President on atomic weapons in the “interim” before a permanent Congressional body could be established — was run by Truman’s co-President and bomb advocate, Jimmy Byrnes. The Committee met for the first time on May 9, 1945, and, three weeks later, recommended that the bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible and without warning. Byrnes also expressed the view, agreed to by the other committee members, that Stalin should not be told about the weapon.

[NOTE TO READER: Next, Leó Szilárd pleads with Jimmy Byrnes to consider how the use of the atom bomb could ignite a potentially catastrophic arms race. Spoiler alert: Byrnes is unmoved.]