After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 12 of 12, or more!)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: When we left you in part 11, it was 1942. General Leslie Groves had been given command of the Manhattan Project and, with an astonishing level of energy and determination, immediately accelerated the pace of bomb making. The rise of Groves would coincide with the sidelining of Leó Szilárd, the person who had single-handedly convinced the U.S. to start atomic research in 1939.]

Q: Why was Leó Szilárd sidelined?

A: As mentioned in Part 1 of this series, General Groves really disliked Szilárd. The feeling was mutual.

Q: Why was the relationship between Szilárd and Groves so terrible?

A: Szilárd had an innate distrust of the military class. Indeed, he admitted “baiting the brass hats,” and classified Groves as pompous, rigid, imperialistic, and a very “big fool.” Groves, who was openly anti-Semitic, thought Szilárd was a Jewish busybody, and judged him the project’s “biggest villain.” Szilárd’s sparkling idea-a-minute intelligence and radical independence unnerved Groves, a brutally on-task engineer with no tolerance for dissent. The one-star brigadier general preferred “quiet, shy and modest” non-Jews, such as Szilárd’s project partner Enrico Fermi. Groves had determined that the fundamental problem with the Hungarian physicist was that he hadn’t played baseball, and therefore had failed to learn the concept of teamwork.

Q: For Szilárd, what were some of the issues inside the Manhattan Project that caused collisions with General Groves?

A: Bomb historian Alex Wellerstein offered this take: “Szilárd thought the military did things badly, and, in the end, that there were some bad people at the top. He didn’t hide his feelings on the matter. Rather, he blatantly told many people them – he feared the American military would assert a dictatorship, would use the bombs in a terrible way, and would jeopardize the future peace of the planet. And, from a certain perspective, he wasn’t too far off the mark. The Manhattan Project was asserting quasi-dictatorial powers during the war (and the bomb did bring with it rigid hierarchies, abnormal secrecy, and a lack of democratic process wherever it went in the Cold War) … they were planning to use the bomb on civilians to make their point (which one can agree with or disagree with as a strategy) … and they were decidedly not interested in any approach to world peace other than building up a large American nuclear arsenal (which in Szilárd’s mind was a path to global suicide).”

Q: If I want to read more from Alex Wellerstein, where would I find it?

A: Mr. Wellerstein has a terrific blog; RESTRICTED DATA: The Nuclear Secrecy blog (https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/about-me/). Below is the cover of his recent book: RESTRICTED DATA: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States.

Q: How did the Szilárd-Groves feud begin?

A: Compartmentalization. Groves demanded it. Szilárd thought it was stupid and said so, repeatedly.

Q: In the context of the Manhattan Project, what did compartmentalization mean?

A: As Robert Jungk wrote, Groves and military authorities “erected invisible walls round every branch of research, so that no department ever knew what any other was doing. Barely a dozen of the 150,000 persons eventually employed on the Manhattan Project were allowed an overall view of the plan as a whole. In fact, only a small number of the staff knew that they were working on the production of an atom bomb at all.”

Q: Why did Szilárd take issue with compartmentalization?

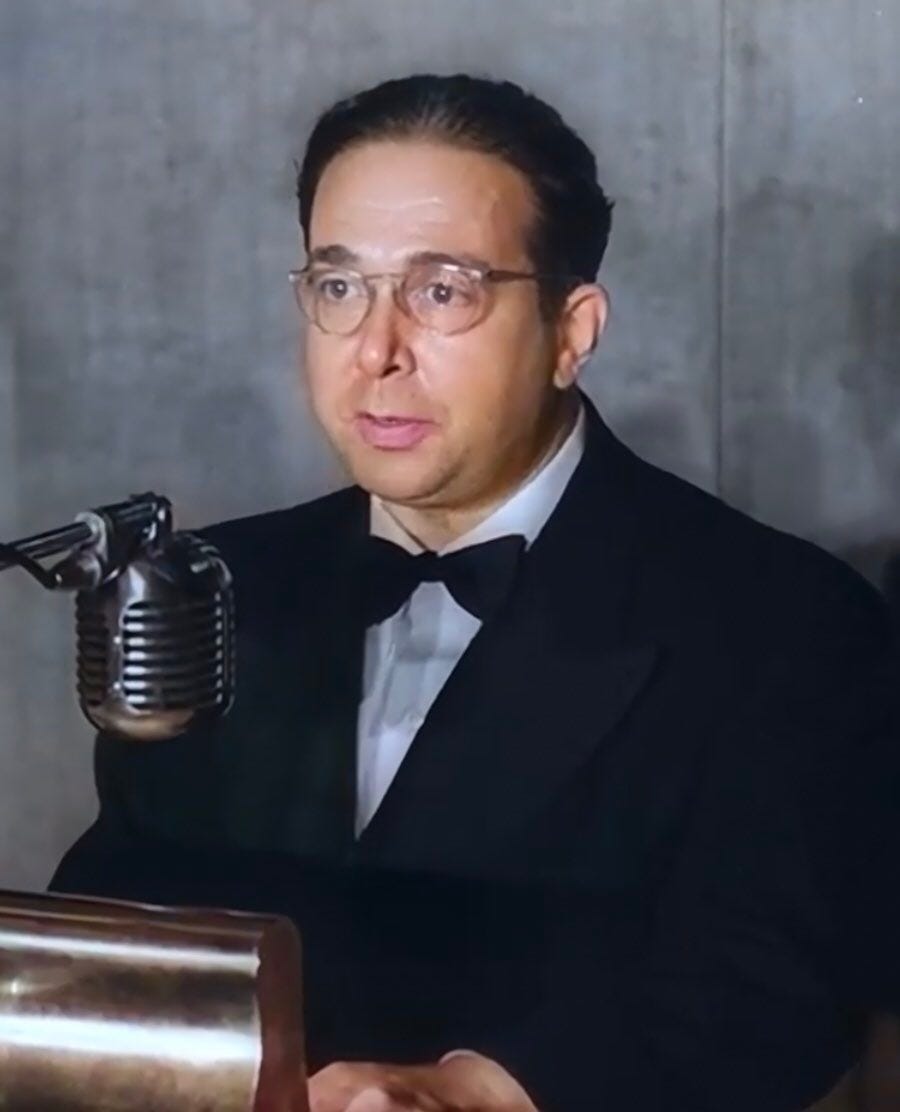

A: For almost three years, from 1939 to 1941, Szilárd was effectively a one-man Manhattan Project trying to get the U.S. government to back bomb research. During that time, he had also badgered reluctant fellow physicists, Fermi in particular, to stop publishing research that could help the Nazis build a bomb. Given his very clear track record – as both the prime mover of the project and the prime mover of establishing extraordinary secrecy – it seemed absurd to Szilárd that, as Groves took control in the fall of 1942, the Army was “compartmentalizing” him. As Szilárd would openly proclaim, compartmentalization was disempowering fertile free thinkers, like himself, in order to empower less-qualified individuals who had the virtue of being more compliant. (Szilárd seen below, from 1945 speech.)

Q: How was compartmentalization disempowering fertile free thinkers?

A: Szilárd would explain how in notes for a meeting with the country’s civilian Science Czar, Vannevar Bush: “The attitude taken toward foreign-born scientists in the early stages of this work had far reaching consequences affecting the attitude of the American-born scientists. Once the general principle that authority and responsibility should be given to those who had the best knowledge and judgement is abandoned by discriminating against foreign-born scientists, it was not possible to uphold the principles with American-born scientists either. If authority is not given to the best men in the field there does not seem to be any compelling reason to give it to the second-best men and one may give it to the third- or fourth- or fifth-best men, whichever of them appears to be the most agreeable on purely subjective grounds.”

Q: How soon did Groves try to sideline Szilárd?

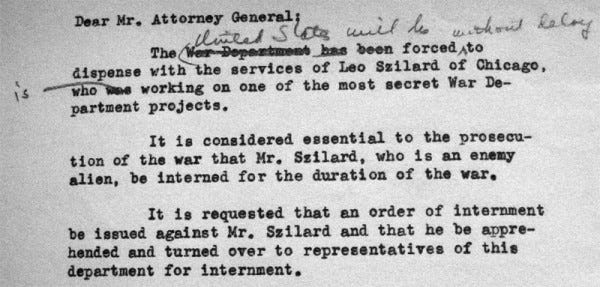

A: A month after taking charge of the Manhattan Project, Groves decided Szilárd needed to be put in jail Hearing, among other things, that Szilárd was a constant critic of compartmentalization, Groves drafted a secret letter, dated October 28, 1942, to be signed by Secretary of War Henry Stimson and sent to the Attorney General. The letter ordered Szilárd to be apprehended and put in prison.

Q: What did the letter say?

A: “Dear Mr. Attorney General: The United States will be forced without delay to dispense with the services of Leó Szilárd of Chicago, who is working on one of the most secret War Department projects. It is considered essential to the prosecution of the war that Mr. Szilárd, who is an enemy alien, be interned for the duration of the war. It is requested that an order of internment be issued against Mr. Szilárd and that he be apprehended and turned over to representatives of this department for internment. Sincerely yours, Secretary of War.” (Letter is below.)

Q: Did the Secretary of War sign the letter?

A: No. But Groves wasn’t done trying to put Szilárd in jail. He assigned an agent to find dirt on the scientist. Without warrants, Szilárd’s mail was opened and his phone was tapped. All of his movements were shadowed.

Q: Did Szilárd know Groves was looking for an excuse to get rid of him?

A: Yes, and the irrepressible Szilárd fought back. “As political dissidents have done in the Soviet Union,” wrote Richard Rhodes, “Szilárd embarked on a careful campaign to negotiate rights by insisting meticulously on the enforcement of his legal rights.” Szilard told Lyman Briggs, head of the Uranium Committee at the Office of Scientific Research and Development, that he wanted to apply for a patent “on the basic inventions which underlie our work on the chain reaction” and indicated he was willing “to assign this patent to the government for such financial compensation as may be deemed fair and equitable.”

Q: What was the government’s reaction to Szilárd raising the issue of a patent on the chain reaction?

A: Szilárd made the request in December 1942. The negotiation with the government proceeded very slowly. When the Los Alamos Laboratory opened in April 1943, Szilárd wasn’t invited to join the group, but it seems he didn’t want to be there, either. (“Nobody could think straight in a place like that,” he claimed.) In June 1943, as Szilárd was becoming a U.S. citizen, Groves demanded that the surveillance continue, writing, “The investigation of Szilárd should be continued despite the barrenness of the results. One letter or phone call once in three months would be sufficient for the passing of vital information.”

Q: Was Szilárd aware he was under strict surveillance?

A: Yes, especially when six FBI agents joined him for breakfast in the drugstore of a Washington D.C. hotel.

Q: Did Groves ever find anything proving Szilárd was a spy?

A: No. But that didn’t keep Groves from having Szilárd dismissed from the Chicago Met Lab. This took place in August 1943. Szilárd was taken off the payroll, required to return all secret documents, and informed that he couldn’t return to the Manhattan Project until the patent issue was resolved.

Q: At the time, were others critical of how Groves treated Szilárd?

A: Yes. Szilárd’s patent attorney, James Hume accused Groves of using Gestapo tactics. “Groves’s actions toward Leó were abominable,” said Hume. “At that time, we thought all the stiff-armed tactics were coming from the Nazis, but I soon discovered that Groves’s actions fitted right into that pattern. That’s the thing we were supposed to be fighting, I thought.” Independent scholar Gene Dannen compared Groves to Richard Nixon. “Szilárd was unquestionably Groves’ top enemy,” Dannen wrote, “and his paranoid obsession with Szilard’s dissent was truly Nixonian … There were, in fact, real spies on the Project, but Groves’ draconian security measures found none of them. Like Nixon, he confused dissent with treason, and focused on the dissenters.”

Q: What did U.S. government ultimately pay Szilárd for the patent related to the chain reaction?

A: $15,416.60. The sum, which Szilárd reluctantly accepted in December 1943, was meant to cover the 20 months when he worked “unpaid and out-of-pocket” at Columbia, plus lawyer’s fees. Szilárd had first asked for $750,000. “Groves was determined to obtain Szilárd’s patent rights by any means,” Dannen wrote, “and he forced Szilárd to choose between giving up his patents or leaving the Project. Szilárd considered leaving the Project to be the same as a soldier deserting his post in wartime, and he felt he had no choice but to stay. If he had left the Project to protect his patent rights, I think it’s almost certain that Groves would have imprisoned him.”

Q: As Szilárd was being sidelined by Groves, were there important developments related to the bomb?

A: Yes. Szilárd’s justification for starting work on a bomb was vanishing. The justification was the fear that the Nazis could beat the U.S. to a nuke. But, by 1943, that fear was subsiding.

Q: Why was the fear subsiding?

A: A Soviet victory in the blood-soaked Battle of Stalingrad appeared to shift World War II in favor of the Allies. During the battle, Stalingrad, a large industrial city on the Volga River, would be turned into a moonscape by months of intense street fighting. Battles were fought inside factories, at railway stations, around city squares. Stalin employed savagery instead of strategy. Red Army soldiers had been issued Order 277, decreeing that defenders of Stalingrad “not take one step back.” Stalin also refused to evacuate civilians.

Q: How did the battle conclude?

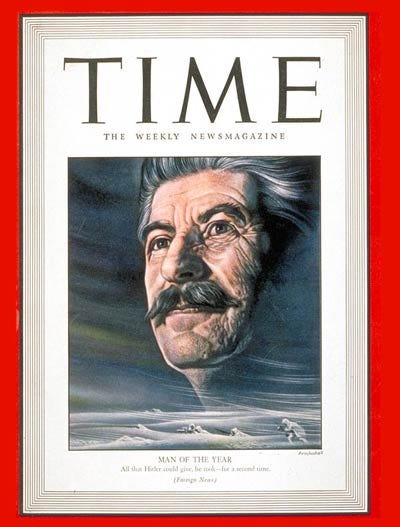

A: On February 2, 1943, surrounded by the Red Army, the German Sixth Army surrendered. The casualty figures were monumental. 800,000 Axis troops (Germans, Romanians, Italians, Hungarians) were killed, wounded or missing. 91,000 Axis troops surrendered – only 5,000 survived the war while in Soviet captivity. Soviet casualties were 1.1 million. An estimated 40,000 Soviet civilians were killed. The Red Army suffered more combat deaths at Stalingrad alone than the U.S. armed forces totaled in the entire war. TIME made Stalin “Man of the Year.”

Q: What was TIME’s justification for making Stalin “Man of the Year”?

A: Assessing Joseph Stalin’s “achievements” in 1942, TIME wrote: “At the beginning of the year, Stalin was in an unenviable spot. During the year before, he had sold over 400,000 miles of territory … Gone was a big fraction ⎼ how large only he knew ⎼ of precious tanks, planes and war equipment … Gone was roughly one-third of Russia’s industrial capacity … Gone was nearly half of Russia’s best farmland. With all this gone, Stalin had to face another full-weight blow from the Nazi war machine … Only Stalin knows how he managed to make 1942 a better year for Russia than 1941. But he did.”

Q: Did the Allies start thinking about winning the war and what victory would look like?

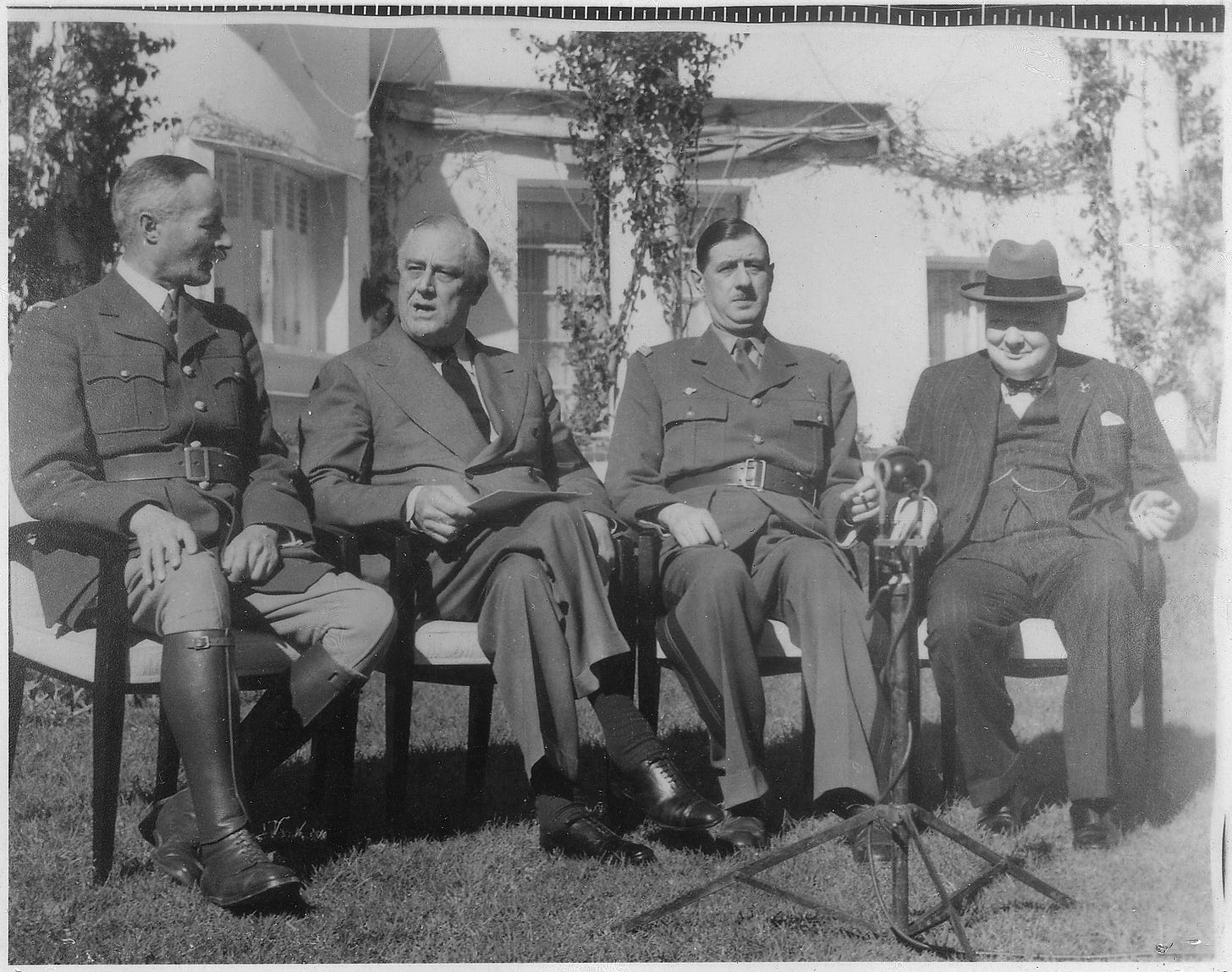

A: Yes. At the 1943 Casablanca Conference (Morocco, January 14-24), Roosevelt and Churchill began to discuss what kind of surrender would be demanded from the Axis powers, but they did not agree on the specifics. (Stalin was invited to the conference, but declined, needing to devote full attention to Soviet offensive actions as the tide of the war seemed to be turning.) However, at the closing press conference in Casablanca, on January 24, the word unconditional slipped out ⎼ largely by accident. FDR demanded the unconditional surrender of Germany, Italy and Japan. “Suddenly, the press conference was on,” Roosevelt said later, “and Winston and I had no time to prepare for it.”

Q: So Roosevelt called for an unconditional surrender by accident?

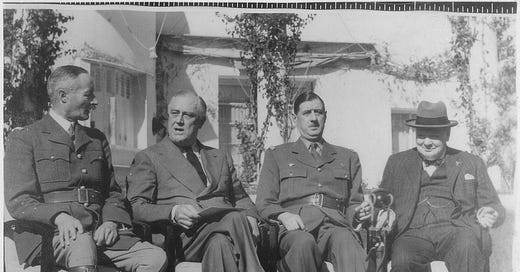

A: Yes. Roosevelt had been thinking of Ulysses Grant because it seemed to him that getting the cooperation of two ornery French generals, Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle, was as hard as arranging a meeting between generals Grant and Lee at the end of the Civil War. “And,” said Roosevelt, “the thought popped into my mind that they had called Grant ‘Old Unconditional Surrender,’ and next thing I knew I said it.” Churchill was taken by surprise, but supported Roosevelt as a show of unity. (Below, from left to right: Giraud, Roosevelt, de Gaulle, and Churchill in Casablanca):

Q: Was there a downside to the requirement of an unconditional surrender?

A: Yes. In 1945, months before the Hiroshima bombing, the Japanese would actively seek a conditional surrender: the condition being retention of the Emperor. However, by that point in the war, the American population had not only been habituated to the idea of an unconditional surrender but, after regularly hearing of Japanese atrocities, fully backed such terms. Harry Truman therefore inherited a mandate of total victory when he succeeded Roosevelt, and, thinking it best not to oppose the “will of the voters,” he acted accordingly.

[NOTE TO READER: Well, this was part 12 of 12. And the author did promise “final answers” in this installment. But the series has also carried the caveat of “or more.” So, there will be part 13 — and probably a few more after that. What’s ahead: As may already be clear, the author sees Leó Szilárd as a heroic figure in the making of the bomb. Szilárd would also demonstrate his heroism in what would be a futile effort to prevent the U.S. from using the bomb. The post-war world would likely have been a more placid place — or at least not one threatened with 24-7 total annihilation — had those in power listened to Leó. How that mistake was made will be the overriding theme in the remainder of this series.]