After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 14 of 12, or more!)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: In Part 13, we concluded with Harry Truman being selected as Franklin Roosevelt’s Vice President for what would be a fourth term. Given FDR’s clearly suspect health, Truman was virtually a President in waiting. The choice of Truman as VP deeply angered Jimmy Byrnes, who thought he deserved the job, had even been told by FDR that he had the job, and, on top of that, had seen the job go to the no-name guy he had schooled in national politics.]

Q: How did FDR treat Harry Truman when Truman became his Vice President?

A: Before Roosevelt’s death, in April 1945, Truman would meet with the President, as David McCullough explained, “exactly twice … and neither time was anything of consequence discussed.” Later, Truman said, “Roosevelt never did talk to me confidentially about the war, or about foreign affairs, or what he had in mind for peace after the war.”

Q: So FDR did not tell Truman about the making of the bomb?

A: No. But Truman knew about the Manhattan Project.

Q: How did he know?

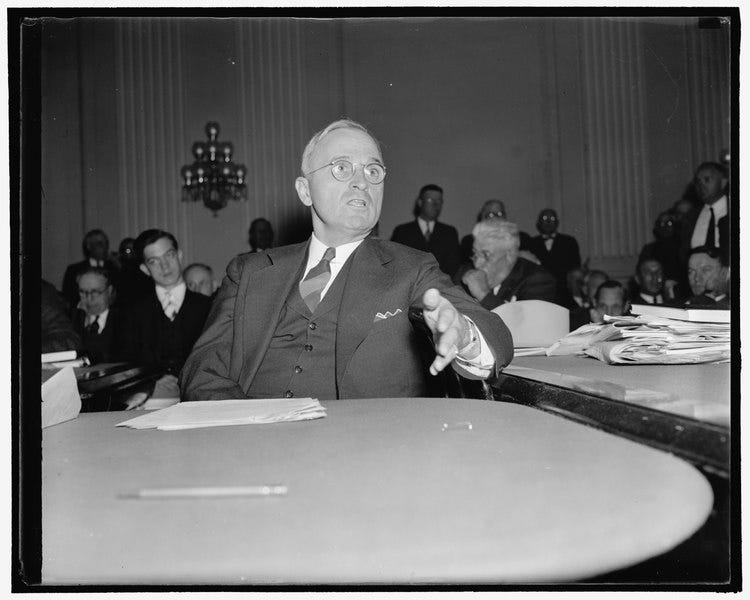

A: In the Senate, Truman was chairman of a watchdog committee – officially known as The Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program. The committee was credited with preventing World War II defense contractors from gouging the government. On February 10, 1941, pre-dating the attack on Pearl Harbor, Truman had made the case for such a committee in a speech that, as the U.S. Senate website wrote, “would forever change his destiny … A former small business owner, Truman cautioned against awarding defense contracts in a way that ‘make[s] the big men bigger and let[s] the little men go out of business or starve to death.’” (Below, Truman, as Missouri Senator):

Q: Why did the speech change Truman’s destiny?

A: The party bosses who pushed for Truman’s selection as VP, in 1944, took into account the positive press he’d received from being seen as leading Congress in curbing and controlling stratospheric spending on arms, in theory saving taxpayers billions of dollars by combating waste and corruption.

Q: When did Truman first learn about the Manhattan Project?

A: On July 17, 1943, acting as the chair of what came to be known, simply, as “The Truman Committee,” he’d call Secretary of War Henry Stimson about the astonishing amount of money being spent on this thing coded as the “Manhattan Project.”

Q: What did Stimson tell Truman at the time?

A: “Now,” Stimson told him, “that’s a matter which I know all about personally, and I am the only one of a group of two or three men in the whole world who know about it.” After a short back and forth in which Stimson told Truman a version of “I’d like to tell you more but then I’d have to kill you,” Truman concluded the conversation by saying, “I herewith see the situation, Mr. Secretary, and you won’t have to say another word to me, that’s all I want to hear.”

Q: While a Senator, did Truman ever get a better idea of the purpose of the Manhattan Project?

A: Yes. As the top watchdog for defense spending, Truman inevitably kept learning more about one of the most, if not the most, expensive defense project in the history of man. On July 15, 1943, referring to the plutonium reactors being built in Hanford, Washington, Truman would blithely compromise national security by writing a letter to an area judge and ex-Senator which revealed that the plant was being constructed “to make a terrific explosion for a secret weapon that will be a wonder.”

Q: If General Groves had found out that Leó Szilárd was writing letters talking about a “terrific explosion from a secret weapon,” that would have been really bad for Leó, right?

A: Indeed. As it turned out, there were many leaks from the ostensibly super top-secret Manhattan Project, and leaks that were far more revealing than Truman’s relatively vague revelation about a wonder weapon. As Gene Dannen noted, there were a) real spies on the Project and b) Groves found none of them, while confusing dissent with treason. In fact, Stalin’s spies were successfully stealing atomic secrets as fast as the Manhattan Project was producing them.

Q: Did other key players assume dissent – or debate – could indicate treason?

A: Yes. Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt.

Q: Did they also want to put Leó Szilárd in jail?

A: No. But they thought about putting Nobel-Prize winner Niels Bohr in jail.

Q: What had Bohr done to alarm Churchill and Roosevelt?

A: Bohr told Churchill and Roosevelt they should let Stalin know about the bomb.

Q: Hadn’t Bohr established his loyalty by helping the U.S. figure out how to make a bomb, while he was at Princeton in 1940?

A: Yes. Bohr’s key insights on uranium were discussed in Parts 3 and 4 of this series. Plus, after the British had staged a daring rescue to get him out of Denmark, in September 1943, Bohr then accepted Oppenheimer’s invitation to visit the New Mexico bomb factory and supply his unsurpassed knowledge of physics. (In Oppenheimer, Bohr is played by Kenneth Branagh.)

Q: Since the Soviets were allies with the Americans and the Brits, wasn’t it somewhat logical for Bohr to suggest that Stalin be told about the bomb?

A: Yes. And, in retrospect, it was actually pointless to keep the secret from the Soviets. Though neither FDR nor Churchill were aware of it, Stalin — as mentioned — was fully educated about the bomb project from his effective espionage efforts. He was also going to be directly told about the bomb’s existence by Truman, at Potsdam in July 1945, although Truman’s admission was brief and oblique.

Q: Why did Bohr think Stalin should know?

A: In April 1944, Bohr went to the Soviet Embassy in London to pick up a letter from top Soviet physicist Peter Kapitsa, who’d met Bohr when both were attached to Cambridge. Kapitsa’s letter invited Bohr to come to the Soviet Union for the remainder of the war. Though there was no reference to the atom bomb, or a Soviet nuclear program, the letter acted to further confirm Bohr’s expectation that the Soviets were developing a bomb. (Below, Bohr on the left, Kapitsa on the right):

Q: For Bohr, what were the implications of learning that the Soviets likely had their own bomb program?

A: “Bohr was concerned about the danger of a postwar nuclear arms race between the western powers and the Soviet Union,” wrote David Holloway. “He had a high opinion of Soviet physics, and did not doubt that the Soviet Union could build its own atomic bomb. He believed that it was therefore imperative for the United States and Britain to inform Stalin about the development of the bomb, without initially divulging technical details. Only in this way might Stalin be persuaded that the United States and Britain were not conspiring against him.”

Q: How did Bohr try to convince Churchill and FDR that they should tell Stalin about the bomb?

A: He spoke to each of them, individually. On May 16, 1944, Churchill’s science advisor, Lord Cherwell, arranged a meeting for Bohr at Downing Street. It was a disaster. Churchill was preoccupied by D-Day preparations and, furthermore, had no interest in discussing international control of nuclear weapons.

Q: How did it go with Roosevelt?

A: Before meeting FDR, Bohr put his ideas into a memorandum, dated July 1944, which, in addition to advocating for international control of atomic weapons, argued for a complete exchange of information, cooperation among scientists, and a guarantee of common security. “Any temporary advantage, however great,” Bohr wrote, “may be outweighed by a perpetual menace to human security.” Bohr met Roosevelt at the White House on August 26, 1944 and, unlike Churchill, the Danish scientist found FDR receptive, to the point that, as Holloway wrote, “[Bohr] prepared a draft letter to Kapitsa and held himself ready to go to Moscow as emissary.”

Q: But Roosevelt changed his mind?

A: Yes.

Q: Why?

A: Because of Churchill, who was able to exploit his tedious power of persuasion with a fading Roosevelt. The Prime Minister and President met from September 11 to September 19, 1944, first in Quebec and then at FDR’s home in Hyde Park, New York. In spite of being a functional alcoholic and smoking eight to ten cigars a day, Churchill was rather indestructible. (He’d live to be 90, dying in 1965.) By contrast, as the Quebec-Hyde Park meeting marathon concluded, FDR had less than a year to live – 205 days to be exact.

Q: Was it clear that Churchill was far more energetic than FDR?

A: Yes. Clementine Churchill, the PM’s wife, was present for the meetings and, in a letter to daughter Mary, wrote how FDR “with all of his genius does not – indeed cannot (partly because of his health and partly because of his makeup) – function round the clock like your Father. I should not think that his mind was pinpointed on the war for more than four hours a day, which is not really enough when one is a supreme war lord.”

Q: What did Churchill and FDR decide should be done about Bohr’s ideas, specifically approaching Stalin about the bomb?

A: While meeting at Hyde Park on September 18, 1944, the two leaders issued a secret memorandum which stated that “enquiries should be made about the activities of Professor Bohr and steps taken to ensure that he is responsible for no leakage of information, particularly to the Russians.” The memo also stated, “The suggestion that the world should be informed regarding T.A. [Tube Alloys, the British codename for the atomic project] with a view to an international agreement regarding the control and usage, is not accepted.”

Q: So, it was decided Stalin was going to be kept in the dark about the bomb?

A: Yes. This secret memo, from a secret meeting — which reflected the wisdom of two non-scientists, who didn’t know the bomb wasn’t actually a secret to Stalin — determined that everything about the bomb had to be “regarded as of the utmost secrecy” until “it might perhaps, after mature consideration, be used against the Japanese, who should be warned that this bombardment will be repeated until they surrender.” (Below. a copy of the Top Secret “Tube Alloys” memo):

Q: Was Bohr put under investigation?

A: Two days after the conclusion of the meetings with Roosevelt, Churchill wrote a letter to Lord Cherwell: “The President and I are much worried about Professor Bohr … He is a great advocate of publicity … The Russian professor has urged him to go to Russia in order to discuss matters. What is all this about? It seems to me Bohr ought to be confined or at any rate made to see that he is very near the edge of mortal crimes. I had not visualized any of this before, though I did not like the man when you showed him to me, with his hair all over his head at Downing Street.”

Q: How did Lord Cherwell respond?

A: He told Churchill that Bohr “is probably the world’s greatest authority on the theoretical science side” and “I have always found Bohr most discreet and conscious of his obligations to England to which he owes a great deal, and only the very strongest evidence would induce me to believe that he had done anything improper in this matter.”

Q: Was that good enough for Churchill?

A: Yes. But, like Groves, Churchill also wasn’t very good at fingering spies and the bulk of the top Soviet assets tied to the Manhattan Project came from Britain. The Soviets were fed details about the bomb from moles inside the British version of the CIA (MI6), and the British version of the FBI (MI5), and the British version of the State Department (the Foreign Office), and by British scientists assigned to work on the Manhattan Project, including at the Los Alamos Lab. While Churchill was fretting about Bohr, his own citizens were providing Stalin with every important secret about the making of the bomb.

Q: Was Roosevelt able to accomplish anything significant during the final months of his life?

A: Yes. At the last Big Three Summit FDR attended, held February 1945 in Yalta, he gained Stalin’s full support for the United Nations. (Below, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at Yalta.)

Q: Where is Yalta?

A: Yalta is on the Crimean Peninsula, with a panoramic view of the Black Sea. The site selection was imposed by Stalin, who had refused to leave the Soviet Union. Churchill said, “If we had spent 10 years on research, we could not have come up with a worse place in the world.” Months earlier, it had been a war zone. The Germans had occupied the Crimean Peninsula in 1941 and weren’t removed until May 1944. Roosevelt stayed at the 116-room Livadia Palace, built in 1911 as a summer residence for Tsar Nicholas II and his family. (By the way, this is also the same Crimea currently in the news. In 2014, the Russians annexed Crimea – and therefore Yalta – from Ukraine.)

Q: How was the establishment of the United Nations ensured at Yalta?

A: Scholar Nicholas Dwyer wrote, “Both issues of the extra Soviet votes and use of the veto were resolved with relative ease after Roosevelt and Stalin spoke face to face. Roosevelt and Stalin compromised at Yalta. Stalin had no illusions that the many Soviet states he claimed to be independent were not, it was simply a method of canceling out American and British influence in the rest of the globe. Roosevelt agreed to add two Soviet republics, instead of all 16, mitigating the damage to the institution's image in America while still giving Stalin something … While the powers could not veto a discussion or resolution being put forth, they could veto the final action of the Security Council, which provided the check Stalin desperately wanted … With the atomic bomb not fully developed, the United States was still counting on Soviet support against Japan.”

Q: Why wasn’t the Soviet Union fighting against Japan?

A: The Soviets and the Japanese were still observing a neutrality pact they had signed on April 13, 1941. At that time, both countries had other military priorities – Stalin was expanding the Soviet empire into the Baltics, the Japanese were expanding into French Indochina and various islands and territories in the South Pacific. Neither was seeking to fight a war on two fronts.

Q: At Yalta, did Stalin agree to join the war against Japan, as the U.S. wished, breaking that Neutrality Pact?

A: Yes. In a secret memorandum, the Soviets agreed to join the war against Japan “two to three months” after Hitler was defeated. The decision served Stalin, as well. He was seeking to regain a sizeable amount of Far East territory lost in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.

Q: Did the U.S. military like the idea of the Russians joining the war against Japan?

A: Yes. When learning about the secret agreement at Yalta, Admiral William Leahy, FDR’s top military advisor, said, “We’ve just saved two million Americans.”

Q: When did Roosevelt announce the establishment of the United Nations?

A: On March 1, 1945, after a long and difficult journey home from the Black Sea resort, FDR proudly told Congress, and, by extension, a national radio audience, that a founding conference for the U.N. was to be held that April, in San Francisco. FDR had been pushed into the chamber in a wheelchair, something he had never permitted before, and was seated in a red cushioned chair behind a wooden table on the dais, putting him at eye level with the members.

Q: How did FDR frame the mission of the U.N.?

A: Making the case, FDR said, “The structure of world peace cannot be the work of one man, or one party, or one Nation. It cannot be just an American peace, or a British peace, or a Russian, a French, or a Chinese peace. It cannot be a peace of large Nations ⎼ or of small Nations. It must be a peace which rests on the cooperative effort of the whole world … There can be no middle ground here. We shall have to take the responsibility for world collaboration, or we shall have to bear the responsibility for another world conflict.”

Q: Is it fair to say that relations between the Allies were in a good place after Yalta?

A: Yes. It wouldn’t last very long, however. At Yalta, Stalin was allowed to make a vague promise to support free elections in Poland. But, just weeks after the summit, it became clear that he was going to try to turn Poland – and all Eastern European nations – into puppet states. This behavior had a lasting blowback effect on Jimmy Byrnes.

Q: The guy Roosevelt didn’t pick to be his VP?

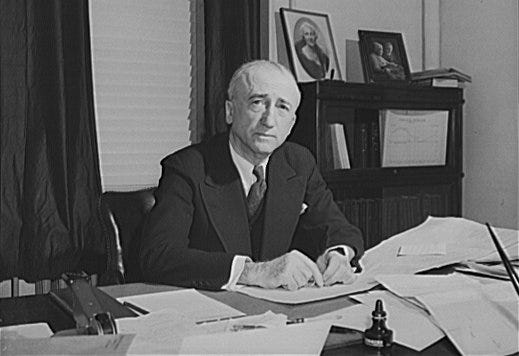

A: Yes. Yalta ended up being bad news for Jimmy Byrnes, the guy who would never forgive FDR for both lying to him about the VP job and then picking the guy he tutored in the Senate, the much less experienced Harry Truman. Perhaps as something of an apology, Roosevelt had asked his wartime “Assistant President” to join him at the Yalta Summit. For Byrnes, this was the first time he had been given a prominent role in U.S. foreign affairs. (Below, Byrnes at his desk in the White House):

Q: Why did Yalta become bad news for Byrnes?

A: A day before the end of the summit, Roosevelt asked Byrnes to fly back alone to the United States, a trip of about 6,700 miles from the Crimean Peninsula. (Roosevelt had elected to take a two-week boat journey.) “Without wasting a minute,” TIME reported on February 26, 1945, “[Jimmy Byrnes] called a press conference. It appeared that [his] role was to be the official interpreter of the Crimea Charter to the U.S. people and Congress.” Roosevelt expected that Byrnes would be a trusted voice, as both a distinguished super achiever who had served in all three branches of government … but yet, not enough of a toadying “yes-man” to be chosen VP.

Q: What did the “official interpreter” of the Crimea Charter tell America?

A: Unfortunately, during that first press conference – and subsequent conversations with Congressmen – Byrnes oversold Yalta’s results, such as the prospect of Polish autonomy. A more experienced player would have known that Stalin didn’t have the slightest intention of observing various commitments listed on the summit’s joint communiqué, which included a very idealistic “Declaration on Liberated Europe,” based on the very idealistic Atlantic Charter – the 1941 Churchill-FDR statement of principles acknowledging “the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.”

Q: Did Stalin ever define his version of “liberating” Europe?

A: Yes. In April 1945, Stalin said, “This war is not as in the past. Whoever occupies a territory also imposes on it his own social system. Everyone imposes his own system as far as his army can reach. It cannot be otherwise. If now there is not a communist government in Paris, this is only because Russia has no an army which can reach Paris in 1945.” As historian Andrew Roberts wrote, “There was effectively nothing that either FDR or Churchill could have done to safeguard political freedom in eastern Europe, and both knew it. Roosevelt certainly tried everything – including straightforward flattery – to try to bring Stalin round to a reasonable stance on any number of post-war issues … but he overestimated what his undoubted aristocratic charm could achieve with the homicidal son of a drunken Georgian cobbler.”

Q: When did Congress and the U.S. public truly know that Jimmy Byrnes had oversold the prospect of Polish autonomy?

A: It didn’t take long. On March 27, 1945, just a month after the conclusion of the Yalta Summit, Lavrenti Beria’s secret police – the NKVD, later the KGB – arrested sixteen leaders of the Polish underground. Under Stalin’s criminal regime, Beria was prized for his expertise in the commission of torture and mass murder. The NKVD transported these top Polish freedom fighters to Moscow, detained them at Lubyanka, the notorious headquarters for Soviet security services, and falsely convicted them of aiding the Germans in a classic Stalin show trial. Most of the sixteen were given significant jail sentences, three died before their release. As the faces of Yalta, Roosevelt and Byrnes were villainized by the Polish-American lobby. (Below, Lavrenti Beria):

Q: Did the Polish-American vote matter for the Democrats?

A: Oh yes. Roosevelt had always counted on deep support from working-class Polish-Americans in Detroit, Chicago and Milwaukee. In November 1944, following the Presidential election, Charles Rozmarek, the head of the new Chicago-based Polish-American Congress, reminded Roosevelt that his organization (representing six million Polish Americans) had helped him win Chicago’s Polish wards by a 3 to 1 margin. Before Yalta, Rozmarek prayed for FDR to be given the “moral courage, strength and health” to insist on self-determination for Poland. Following Yalta, Rozmarek was offering invective instead of prayers, calling what happened at the summit “a betrayal in the Crimea” and “an injustice … committed not just against Poland but also against the United States.” The right-wing Chicago Tribune would soon exploit criticism of the Yalta agreement to argue that voting for Democrats would provide “encouragement to continue the policies of loot, starvation, and exile that have brought despair to the peoples of Poland.”

[NOTE TO READER: Next, the death of Roosevelt produces a two-headed Presidency.]