After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 15 of 12, or more!)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: At the conclusion of Part 14, Stalin was in the process of turning Poland into a puppet state. This became a political liability for the Roosevelt Administration, and, in particular, for top advisor Jimmy Byrnes, because Byrnes had returned from the Big Three Yalta Summit (FDR, Churchill, Stalin) and told the public that Stalin wasn’t going to turn Poland into a puppet state. This misjudgment would haunt Byrnes — and play a role in his push to use the atomic bomb. Meanwhile, by the spring of 1945, the war in Europe was about to conclude. One indicator was Adolf Hitler’s location. On January 16, 1945, he had retreated into a Berlin bunker. He would never leave and died on April 30, 1945, committing suicide. As for the war against Japan, a top Air Force general was confident it would over in a matter of months.]

Q: Who was the general predicting Japan’s defeat in a matter of months?

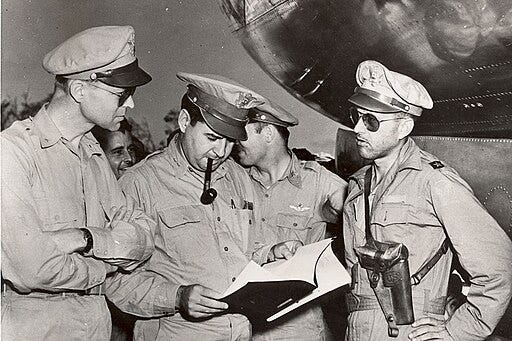

A: Curtis LeMay. On April 15, 1945, LeMay told the Associated Press that “destruction of Japan’s industry by air blows alone” was possible. Later, LeMay would recall a spring 1945 visit by Hap Arnold, the top U.S. Air Force commander. General Arnold had asked when the war was going to end. “We went back to some of the charts,” said LeMay, “we had been showing him the rate of activity, the targets we were hitting, and it was completely evident that we were running out of targets along in September and by October there really wouldn’t be much to work on, except probably railroads or something of that sort. So we felt that if there were no targets left in Japan, certainly there probably wouldn’t be much war left.” (LeMay is below, second from left, with pipe):

Q: Why was LeMay so optimistic about air power being enough to defeat Japan?

A: Because of the apparent effectiveness of firebombing, a campaign of turning cities into ashes, which, in the Pacific, was fully demonstrated on March 10, 1945, when 334 B-29s firebombed Tokyo. The tactic created a kind of man-made natural disaster. The primary weapon — a cluster bomb containing a mixture of napalm and white phosphorous — was designed to ignite on impact. In the Tokyo assault, the city’s very flammable wood and paper houses were lit up with a “flaming dew.” As the flames spread, invisible tornados of boiling heat emerged from suddenly violent air.

Q: What was the result of the firebombing of Tokyo?

A: Between 100,000 and 200,000 men, women and children may have been killed; perhaps a million more were wounded; a million were made homeless. Later, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey estimated that, in the six-hour March 9-10, 1945 bombardment, more people had lost their lives than any equivalent period “in the history of man.” In Air Power, Michael Sherry wrote, "The mechanisms of death were so multiple and simultaneous — oxygen deficiency and carbon monoxide poisoning, radiant heat and direct flames, debris and the trampling feet of stampeding crowds — that causes of death were later hard to ascertain.” (Below, Tokyo after the March 9-10, 1945 bombing):

Q: Is it correct to assume that other Japanese cities were being attacked?

A: Yes. Two to three cities were being destroyed every week. On March 16, 1945, a week after the cataclysmic Tokyo bombing, Kobe was attacked by 331 B-29s. The resulting firestorm destroyed roughly half the city, killed 8,000, and left 650,000 homeless. Tokyo was repeatedly bombed. After May 26, 1945 raid, the U.S. determined that 50 percent of Japan’s largest city had now been destroyed and it was taken off the target list. By the end of the war, the U.S. would level almost 70 Japanese cities. LeMay later said, “I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal, Fortunately, we were on the winning side.”

Q: Were there any critics of firebombing in the U.S.?

A: Leó Szilárd was one of them. With the Nazis heading toward defeat, Szilárd was already among many Manhattan Project scientists who began to wonder why there was a need to use the atom bomb. The Japanese were not a threat to produce one. Szilárd’s stance was intensified by his moral revulsion with the start of firebombing in Japan. During the war, the U.S. Air Force had steadily defined deviance down to a tolerance for incinerating civilians. “Throughout the spring and summer of 1945,” wrote Selden Mark, “the U.S. air war in Japan reached an intensity that is still perhaps unrivaled in the magnitude of human slaughter. That moment was a product of the combination of technological breakthroughs, American nationalism, and the erosion of moral and political scruples pertaining to the killing of civilians.” Szilárd remembered how Roosevelt had once found the bombing of civilians revolting (mentioned in part 7 of this series).

Q: For those of us who might not have read all the installments, what did Roosevelt say and how did that affect Szilárd?

A: Here’s Szilárd: “By and large, governments are guided by considerations of expediency, rather than by moral considerations. And this, I think, is a universal law of how governments act. But prior to the war, I had the illusion that, up to a point, the American Government was different … In 1939, President Roosevelt warned the belligerents against using bombs against the inhabited cities, and this I thought was perfectly fitting and natural. Then, during the war, without any explanation, we began to use incendiary bombs against the cities of Japan. This was disturbing to me and it was disturbing to many of my friends.”

Q: Was the United States the first to use firebombing in World War II?

A: No. The Nazis were the first, using some 36,000 incendiary bombs in the November 14, 1940 attack on Coventry, an English industrial city of 200,000. The Luftwaffe used 515 bombers and erased the city center. Coventry’s 79 air-raid shelters limited casualties to 2,000 dead and wounded. After the bombing, Reich Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, coined a new verb to describe total destruction of the enemy: coventrieren – to Coventrate. By the conclusion of a civilian bombing campaign known as “the Blitz,” the Germans had destroyed more than 250,000 homes, left a million homeless, and killed 43,000 British citizens. In 1942, the British decided to begin firebombing the Germans, shifting from “precision bombing” to what was called “area bombing.”

Q: Area bombing?

A: “Area bombing” was a euphemism for “carpet bombing,” or the indiscriminate bombing of civilians and civilian targets. The man in charge was Sir Arthur Harris, soon to be known as “Butcher” Harris. His motto: “Moderation in war is imbecility.” In the early British bombing raids, too many targets were missed and nearly half of the RAF crews were getting killed by German air defenses. To remedy the issue with accuracy and vulnerability, Harris instituted ruthless and prodigious nighttime “area bombing,” using as many 1,000 bombers per mission. Harris and his colleagues also carefully studied “Incendiarism.” Types of German roofs and the thickness of wood beams were tested. Nighttime air raids were coupled with incendiary devices. Attacks often lasted for days. (Below, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris):

Q: Did U.S. bombers join the British in firebombing attacks?

A: Yes, for example, Operation Gomorrah. The RAF and U.S. Air Force firebombed Hamburg for 10 consecutive days, starting July 25, 1943. The firestorms created a temperature of 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit. At least 37,000 were killed. Doctors estimated the number of dead by counting piles of human ash amid the debris. Hamburg survivor Anne-Lies Schmidt said: “The smallest children lay like fried eels on the pavement. Even in death they showed signs of how they must have suffered ⎼ their hands and arms stretched out as if to protect themselves from the pitiless heat.”

Q: Did anyone publicly criticize the firebombing campaigns?

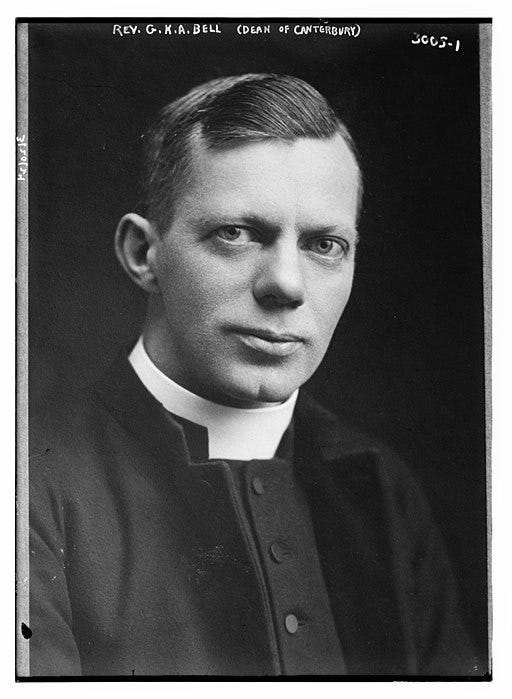

A: Yes. George Bell, the Bishop of Chichester and a member of the House of Lords, was a vocal opponent of “area bombing.” On February 9, 1944, Bell addressed the House of Lords: “Why is there this blindness to the psychological side? Why is there this inability to reckon with the moral and spiritual facts? Why is there this forgetfulness of the ideals by which our cause is inspired? How can the War Cabinet fail to see that this progressive devastation of cities is threatening the roots of civilization? How can they be blind to the harvest of even fiercer warring and desolation, even in this country, to which the present destruction will inevitably lead when the members of the War Cabinet have long passed to their rest? … This is an extraordinarily solemn moment. What we do in war ⎼ which, after all, lasts a comparatively short time ⎼ affects the whole character of peace, which covers a much longer period.” (Below, Rev. George Bell):

Q: Was the bombing of civilians effective?

A: No. “The bombing of cities turns out to have been an inordinate waste of bombs and of bombing,” wrote Bernard Brodie in 1950. He added: “What we have learned from the German experience is this: If we had to do the business all over again with the same weapons, we could do in a few months what in fact took us two years, and we would do it with far less destruction of urban areas and of civilian lives than occurred in Germany in the Second World War.” As for how the bombing affected the morale of Japanese citizens, “ideological mobilization and control was such,” Selden Mark observed, “that there are no signs of resistance to the government’s suicidal perpetuation of the war at any time during the bombing campaign. Whatever the suffering, most Japanese then and subsequently appear to have accepted the legitimacy of the decision to continue fighting a hopeless war.”

Q: Did Szilárd do anything about his objection to the firebombing of cities?

A: Yes. As Le May’s firebombing was being touted in the American press, Szilárd wanted to bring his objections and fears to President Roosevelt. Once again, he would use Albert Einstein to get the President’s attention – but, this time, Szilárd’s purpose in teaming with Einstein was to urge that the atom bomb not be used.

Q: In 1939, Szilárd and Einstein had told FDR that building the bomb was an urgent necessity. But in 1945, with the bomb nearing completion, Szilárd wanted to use Einstein to give Roosevelt the opposite advice?

A: Yes. In 1939, Szilárd and Einstein had sounded the alarm to build an atomic bomb because Hitler had the means and the manpower to make one of his own. But by the spring of 1945, that rationale was no longer valid. There was no imminent atomic threat from any other nation. The bomb was no longer needed to deter Hitler. If it were to be used, as Alex Wellerstein noted, it would be as a “first-strike” weapon on a Japan that was becoming increasingly defenseless. In the Pacific, Japanese cities were rapidly being immolated. Szilárd thought the United States was “moving along a road leading to the destruction of the strong position hitherto occupied in the world.”

Q: What are the details about this 1945 Einstein-Szilárd summit?

A: “Szilárd arrived by train in Princeton on March 23, 1945,” wrote Szilárd biographer William Lanouette, “and walked the few blocks to the white clapboard house on Mercer Street where Einstein lived. The two friends met in the study, a sunny room that looked onto a back garden and lawn.”

Q: Could Szilárd provide Einstein with any details about the bomb?

A: No. By this juncture, Einstein had long been excluded from any discussion of nuclear development – denied a security clearance by Hoover’s FBI before America entered the war (referenced in part 9 of this series). Describing the visit, Szilárd later wrote, “I went to see Einstein, and I asked him to write me a letter of introduction, even though I could only tell him that there was trouble ahead, but I couldn’t tell him what the nature of the trouble was.” Einstein agreed to write what would be his third letter to Roosevelt related to the atom bomb — although, this time, not referencing the weapon. (Einstein’s two other letters to FDR are discussed in parts 6 and 8 of this series.)

Q: What did the letter say?

A: Dated March 25, 1945, Einstein’s letter of introduction read, in part: “The terms of secrecy under which Dr. Szilárd is working at present do not permit him to give me information about his work; however, I understand that he now is greatly concerned about the lack of adequate contact between scientists who are doing this work and those members of your Cabinet who are responsible for formulating policy. In the circumstances I consider it my duty to give Dr. Szilárd this introduction and I wish to express the hope that you will be able to give his presentation of the case your personal attention. Very truly yours, (A. Einstein).” In addition, Szilárd wrote a memo to accompany the Einstein letter, which, in part, proposed the creation of a cabinet-level committee of scientists empowered to play a central role in nuclear policy.

Q: What was Szilárd’s plan for getting the documents to Roosevelt?

A: He wrote a letter to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. She replied quickly and proposed a meeting at her Manhattan apartment on May 8, 1945. But before that meeting could occur, major developments began outpacing Szilárd. On March 27, 1945, as William Lanouette noted, “General Leslie Groves wrote a memo of his own, declaring that he expected the A-bomb to end the war in the Pacific, thereby justifying the project.” On April 12, 1945, there was a bulletin out of Warm Springs, Georgia. Franklin Roosevelt was dead, age 63.

Q: Why was Roosevelt in Warm Springs when he died?

A: As the Roosevelt Presidential Library detailed, “On March 29, 1945, FDR left the White House for the last time on a trip to Warm Springs, Georgia. He had first visited Warm Springs in the mid-1920s after hearing that the waters there had healing powers. He hoped they would help him regain the use of his legs which were left paralyzed from a polio attack in 1921. The cottage where he stayed became known as the ‘Little White House,’ thanks to his frequent visits as president. It was here that FDR went in April 1945 to rest and rejuvenate following the pressures of the 1944 campaign, the Yalta Conference, and the continued war effort. On April 12, 1945, while sitting for a portrait by painter Elizabeth Shoumatoff, FDR suffered a massive stroke. He died a few hours later having never regained consciousness.”

Q: When FDR died, how long had Harry Truman served as Vice President?

A: 82 days.

Q: What was Truman’s first major decision as President.

A: He gave Jimmy Byrnes the same kind of license that George W. Bush gave to Dick Cheney. (Below, left to right: Churchill, Truman and Byrnes):

Q: Did Byrnes become the Vice President?

A: No. In 1945, a Vice Presidential vacancy wasn’t filled until the next presidential election, which was 1948. Therefore, the Secretary of State was the next in the line of succession. Truman asked Byrnes to be Secretary of State either on April 13, 1945, his first full day as President, or shortly thereafter. When the appointment became official, on July 3, 1945, Byrnes was, like Cheney, next in the line of succession. (Congress would alter the order of Presidential succession on July 18, 1947. Preferring that an “elected” official be placed after the VP – instead of a “non-elected” Cabinet member – the new law put the Speaker of the House as “second” in the line of succession.)

Q: Did Byrnes play a role in the Truman Administration before he was officially named Secretary of State, in July 1945?

A: Yes. Immediately after Truman assumed the Presidency, Byrnes became his chief foreign policy advisor – and his chief advisor, period. Like Dick Cheney, Byrnes became an unofficial co-President who wielded power in shadowy ways.

Q: Why did Truman more or less create a co-Presidency?

A: Byrnes was a more accomplished Washington insider — another comparison with Cheney. Truman, even upon being elevated to the Presidency, judged Byrnes to be the superior figure, deserving significant respect and attention. The relationship had begun with an extreme power imbalance, in 1934, when Truman was a rookie in the Senate and Byrnes was one of the chamber’s most powerful figures. By the way, Byrnes also had no doubt that he was the clearly smarter and savvier party in the relationship. Matthew Connolly, who was Truman’s appointments secretary, verified the imbalance. “Mr. Byrnes came from South Carolina,” said Connolly, “and talked to Mr. Truman and immediately decided that he would take over. Mr. Truman to Mr. Byrnes, I’m afraid, was a nonentity, as Mr. Byrnes thought he had superior intelligence. Mr. Truman was completely loyal to Senator Byrnes because of the Senate association.”

Q: Metaphorically, hadn’t the sky fallen on Truman? Didn’t he need all the help he could get?

A: That’s also true. The U.S. was experiencing a profound leadership transition, from a self-assured, visionary President of unparalleled experience, elected a record four times, to a new Commander-in-Chief faced with on-the-job training during the biggest war of all time. “Truman seemed out of his league,” wrote Alex Wellerstein, “and overly dependent on advisors lobbying for position.” And no advisor had a better resume than Jimmy Byrnes – a Master of the Senate, a Supreme Court Justice, and FDR’s World War II “Assistant President” in charge of domestic affairs.

[NOTE TO READER: Next, Harry Truman and Jimmy Byrnes envision “atomic diplomacy” being used to control Stalin. But, failing, they ultimately jump start a five-decade Cold War with the Soviet Union.]