After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 20 of 12 – and maybe one more?)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: In Chapter 19, we discussed how “co-Presidents” Jimmy Byrnes and Harry Truman rolled the dice on using the bomb to achieve two desired goals: to keep the Soviets out of the war against Japan and to compel the Japanese to accept an unconditional surrender. However, this required a race to use the bomb, since Japan was clearly nearing defeat. Truman gave the order to use this weapon from science fiction on July 25, 1945. It was ready to be deployed on August 1, 1945 — but a typhoon crossing Japan kept the plane on the ground. The bomb would get dropped, five days later, but the gamble would fail — the war didn’t end on the terms so feverishly desired by Truman and Byrnes. Further, this short-sighted judgment by America’s two most powerful players in 1945 would pave the way for the existential nuclear peril that is still with us today, nearly 80 years after the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.]

Q: What were the dimensions of the first atomic weapon?

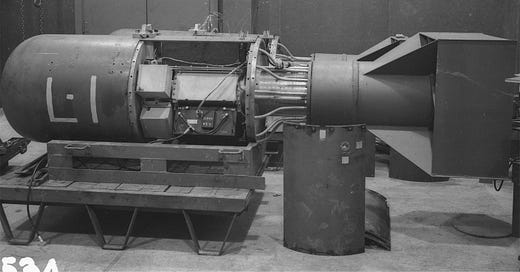

A: Codenamed “Little Boy,” it was 10 feet long, 28 inches in diameter, and weighed 9,000 pounds. In this gun-type device, critical mass was achieved by using a gun barrel to fire a sub-critical uranium projectile at a sub-critical uranium target, triggering an explosion. The bang fused projectile and target, established criticality, and started a chain reaction. As Atomic Archive noted, “Testing was out of the question since producing ‘Little Boy’ had used all of the purified U-235 produced to date; therefore, no other bomb like it has ever been built.” The bomb used approximately 140 pounds of highly-enriched uranium — accumulated by painstakingly extracting the isotope U-235 under the uncompromising mandate of total secrecy, over two years of 24-7 shifts, by hundreds of scientists and thousands of workers, stationed at giant, never-seen-before facilities that regularly fizzled and required constant massaging. (Find more on the enrichment process in chapters 8 and 11 of the series. “Little Boy” is below):

Q: What occurred when the bomb was detonated over Hiroshima, on August 6, 1945?

A: In the first billionth of a second after the detonation of the Little Boy atomic bomb, the temperature at the burst point in Hiroshima was 60 million degrees, ten thousand times hotter than the sun. Spontaneous combustion of human beings occurred at a distance of over 2,000 yards. Passengers in a tram near ground zero were reduced to a pile of black cinder. At a military base, the shadows of soldiers, literally evaporated, were etched on the training ground. Hundreds who sought shelter in the city’s water basins were boiled alive. (Below, scenes from immediate aftermath of Hiroshima atom bomb):

Q: What were the casualties and the damage?

A: There are only estimates, because, given the scope of the immediate devastation, plus the lingering, lethal and little understood after effects, it was possible only to make educated guesses. Here’s one estimate: In a city of 260,000, a quarter were killed immediately, 66,000; another 70,000 were injured; 68,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed. Only three of the 55 hospitals and First Aid stations remained operational. Out of 200 physicians in the city, 180 were either dead or injured. American soldiers were also killed by the bomb.

Q: How many U.S. soldiers were killed by the bomb?

A: In Hiroshima, 12 American prisoners of war were interned at a military police headquarters, just 437 yards from the epicenter of the atomic blast. It is believed ten were killed instantly. The remaining two prisoners reportedly survived by diving into a cesspool, but died days later of radiations poisoning.

Q: How was the information about the U.S. soldiers confirmed?

A: In 1945, after the conclusion of the war, a Japanese military policeman was summoned to General MacArthur’s Tokyo headquarters and confirmed that, in fact, American prisoners had been killed by an American bomb. However, families of the deceased were only told that the men had died in Japan, nothing more. Even when secret War Department documents about the Hiroshima POWs were declassified in 1970, the Pentagon continued to deny the story.

Q: How much radiation was triggered by the Hiroshima atom bomb?

A: An enormous amount. Less than two hours after the bomb exploded, a “black rain,” dark in color and sticky, fell on the city for three hours. The precipitation was the product of the bomb’s dust cloud, and was highly radioactive. There were reports that some survivors, desperately parched by the city’s heat and fires, opened their mouths to the sky to drink the rain.

Q: For the surviving population, could there be two distinct — albeit sometimes simultaneous — injuries from the bomb: damage from the blast and radiation poisoning?

A: Yes. In the Asia-Pacific Journal, Richard Tanter detailed how victims “on filthy tatami mats among the rubble were being ravaged by the effects of massive blast and primary and secondary burn trauma combined with advanced stages of radiation illnesses.” Tanter wrote that the symptoms of radiation illness included: “fever, nausea, hemorrhagic stools and diathesis (spontaneous bleeding, from mouth, rectum, urethra and lungs) … epilation (loss of hair) … purpura (bleeding under the skin, producing purple spots) … and gingivitis and tonsillitis leading to swelling, and, eventually, hemorrhaging of gums and soft membranes.” Tanter added: “In many cases, without effective drugs, large burns and the hemorrhaging parts of the body had turned gangrenous. Recovery was inhibited by the effects of widespread malnutrition, resulting from the cumulative effects of long-term wartime shortages and the Allied blockade of the past year.” (Below, victims of Hiroshima atomic attack):

Q: Taking into account deaths from radiation poisoning after the detonation, is there an estimate for the total number of dead from the Hiroshima bomb?

A: “The United States military estimated that around 70,000 people died at Hiroshima,” wrote Alex Wellerstein in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, “though later independent estimates argued that the actual number was 140,000 dead.”

Q: How did the American public hear about the Hiroshima attack?

A: As the CONELRAD blog noted, “The American public was first introduced to the awesome reality of the atomic bomb courtesy of an Associated Press bulletin transmitted on August 6th, 1945 at 11:03 AM Eastern War Time. Within hours of this historic dispatch, the bar at the Washington Press Club was offering a gin and Pernod concoction dubbed the ‘Atomic Cocktail.’”

Q: Did President Truman make an announcement?

A: The bomb was dropped before Truman got back to Washington from the Potsdam Conference. On August 6, 1945, he was still on the U.S.S. Augusta. In a pre-written statement revealing the new weapon, Truman said: “We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city … It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

Q: In short, Truman was still insisting that the Japanese accept an unconditional surrender?

A: Yes. And he was also hoping that such a surrender would happen soon enough to keep the Soviets from joining the war against Japan.

Q: How did Japan react after the atom bomb was used on Hiroshima?

A: “While senior Japanese officers did not dispute the theoretical possibility of such weapons,” wrote Richard Frank, “they refused to concede that the Americans had vaulted over the tremendous practical problems to create an atomic bomb.” One Japanese Admiral speculated that perhaps it had only been possible for the U.S. to make one nuclear device — but no more. General Leslie Groves and other military figures — anticipating such doubt, and therefore the likelihood that more convincing would be required — had two more atomic weapons in waiting and, further, the U.S. “Army Air Force” was ready to prepare at least another 12 bombs in the following months. (A technical point: In World War II, the Air Force was a component of the Army. It became a separate branch of the U.S. Armed Forces shortly after the war, in 1947.)

Q: Did Truman need to provide an order for the dropping of additional atom bombs?

A: No. “No further orders were required for the [second atomic] attack,” the Dept. of Energy wrote, “Truman's order of July 25th had authorized the dropping of additional bombs as soon as they were ready.”

Q: Was there a scheduled date for the second atomic bomb?

A: To get ahead of bad weather, the date was moved up from August 11, 1945 to August 9, which is when the Nagasaki atomic attack would occur. A third atomic bomb was scheduled to be dropped on August 19, 1945.

Q: Is it possible that Japan’s leaders were becoming numb to city-wrecking missions by American bombers?

A: In Foreign Policy, Ward Wilson wrote, “It is, after all, difficult to distinguish a single drop of rain in the midst of a hurricane … In the summer of 1945, the U.S. Army Air Force carried out one of the most intense campaigns of city destruction in the history of the world … In the midst of this cascade of destruction, it would not be surprising if this or that individual attack failed to make much of an impression — even if it was carried out with a remarkable new type of weapon.”

Q: As mentioned in part 15 of this series, Air Force General Curtis LeMay had begun a firebombing campaign on March 10, 1945. By August, what was the status of that campaign?

A: As Wilson noted, “In the three weeks prior to Hiroshima, 26 cities were attacked by the U.S. Army Air Force. Of these, eight — or almost a third — were as completely or more completely destroyed than Hiroshima (in terms of the percentage of the city destroyed). The fact that Japan had 68 cities destroyed in the summer of 1945 poses a serious challenge for people who want to make the bombing of Hiroshima the cause of Japan’s surrender. The question is: If they surrendered because a city was destroyed, why didn’t they surrender when those other 66 cities were destroyed?”

Q: In other words, Truman’s threat of a “rain of ruin” wasn’t new and the Japanese were apparently prepared to watch all of their cities get flattened?

A: Yes. “Japan’s leaders consistently displayed disinterest in the city bombing,” Wilson wrote, and “by the time Hiroshima was hit, they were certainly right to see city bombing as an unimportant sideshow, in terms of strategic impact. When Truman famously threatened to visit a ‘rain of ruin’ on Japanese cities if Japan did not surrender, few people in the United States realized that there was very little left to destroy.”

Q: So, the Hiroshima bomb didn’t convince the Japanese to even consider accepting an unconditional surrender?

A: The bomb did not. Instead, the Japanese made another appeal to the Soviets. On August 7, 1945, one day after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo sent an urgent telegram to Japan’s Russian ambassador, Naotake Sato, to seek an immediate appointment with the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov. The terribly naive Japanese, still being “lulled to sleep by the Russians,” had been asking Stalin to meet with Emperor Hirohito’s special envoy, Prince Fumimaro Konoe, the former Prime Minister. “This meant,” wrote Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, “that despite the Hiroshima bomb, Japan continued to rely on Moscow’s mediation.”

Q: What did the Japanese hope to get from Stalin?

A: At the very least, terms of surrender that would protect the Emperor. But Japan’s leaders, as Wilson wrote, also “hoped that they might be able to figure out a way to avoid war crimes trials, keep their form of government, and keep some of the territories they’d conquered: Korea, Vietnam, Burma, parts of Malaysia and Indonesia, a large portion of eastern China, and numerous islands in the Pacific.”

Q: What was the reaction to the bomb in Moscow?

A: “I think Stalin and the leadership basically saw the atomic bombing of Hiroshima as directed against the Soviet Union,” said David Holloway, author of Stalin and The Bomb. “They believed that the war with Japan would be over quickly. Of course, the Soviet Union was moving troops to the Far East in order to enter the war with Japan … So bombing Hiroshima was seen as something unnecessary because it was clear that Japan would be defeated … So yes, it was seen very much as directed against the Soviet Union, not only in order to deprive the Soviet Union of gains in the Far East, but generally to intimidate the Soviet Union.”

Q: The Soviet entry into the Pacific War is discussed in part 7 of the series. Did Hiroshima accelerate Stalin’s plan to attack Japan’s Far East territories?

A: Yes. Stalin moved up the planned attack by two days. He had returned to Moscow from the Potsdam Conference on the evening of August 5, 1945. He learned about the Hiroshima bomb about 24 hours later. On August 7, at 2:30 pm, less than 48 hours after getting back from Germany, Stalin signed an order to begin the invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria on August 9, 1945, at midnight.

Q: When did Americans begin to get a sense of the devastation caused by the Hiroshima atomic bomb?

A: On August 8, 1945, just two days after the bomb was dropped, the Hearst News Service published an article by Dr. Harold Jacobson, a Manhattan Project physicist. He predicted that Hiroshima would remain contaminated by radiation for seventy years, resemble “our conception of the moon,” and anyone who chose to visit the city would be radiated and “die in the same way victims of leukemia die.” Following publication, military officials visited Jacobsen at his office in New York and threatened to prosecute him under the Espionage Act. He was later questioned by the FBI. The Pentagon had Robert Oppenheimer refute Jacobsen’s assertions. Oppenheimer assured the public that there was “no appreciable radioactivity on the ground in Hiroshima and what little there was decayed very rapidly.” Eventually. Dr. Jacobsen walked back his remarks and made clear they were based only on his assumptions.

Q: When did the Soviet Union officially declare war on Japan?

A: On August 8, 1945, in Moscow, Japan’s Russian Ambassador, Naotake Sato, was asked to attend a 5 p.m. meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Molotov at the Foreign Commissariat. “When the ambassador arrived at the designated time,” wrote Hasegawa, “Molotov interrupted Sato’s greetings, and proceeded to read the Soviet declaration of war. The declaration explained that the Allies had asked the Soviet Government to enter the war against Japan, and to join the Potsdam ultimatum. It further stated that since Japan had rejected this ultimatum, the Soviet Government considered itself, ‘as of August 9, in a state of war with Japan’ … Stalin succeeded in joining the war in the nick of time.”

Q: Did the U.S., or any of the Allies, ask the Soviet Government to enter the war against Japan and join the Potsdam ultimatum?

A: Heck no. That was a whooping lie. In fact, as repeatedly noted in this series, Truman and Byrnes had raced to use the bomb for two chief aims: to 1) force the Japanese to immediately accept an unconditional surrender and, thereby, 2) end the war before the Soviets could get in it. The gamble on using the bomb for political advantage — domestic and foreign — was backfiring.

Q: What was Japan facing when the Soviets entered the war in the Pacific?

A: As detailed by U.S. Colonel John Pack, “The Soviets attacked unexpectedly during the rainy season with nearly 80 divisions totaling more than 1.5 million men against 31 Japanese divisions in Manchuria and Korea. Although the Kwangtung Army could have potentially mobilized more than a million soldiers, never more than 300,000 joined the fight. While many of the Soviet divisions were first class units transferred from the western front, the Japanese defended Manchuria with a garrison army, an army of occupation since 1932. In numbers, the Soviets had 25,000 artillery pieces, 5,500 tanks, and 4,370 aircraft against Japan’s 5,360 artillery tubes, 1,115 tanks, and 1,800 aircraft.” (Below, conquering Red Army troops in 1945, at the throne of Puyi, the last Chinese Emperor, who had been ruling northeast China as a Japanese puppet):

Q: For Japan, how much of a shock was the Soviet invasion?

A: As Wilson wrote, “Once the Soviet Union had declared war, Stalin could no longer act as a mediator — he was now a belligerent. So the diplomatic option was wiped out by the Soviet move. The effect on the military situation was equally dramatic. Most of Japan’s best troops had been shifted to the southern part of the home islands. Japan’s military had correctly guessed that the likely first target of an American invasion would be the southernmost island of Kyushu. The once proud Kwangtung army in Manchuria, for example, was a shell of its former self because its best units had been shifted away to defend Japan itself. When the Russians invaded Manchuria, they sliced through what had once been an elite army and many Russian units only stopped when they ran out of gas.”

Q: More specifically, how did the Japanese leadership react to the August 9, 1945 Soviet entry into the war?

A: As Hasegawa wrote, “The Supreme War Council, which had not been called even after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, was immediately summoned after the Soviet invasion.” (The Council was comprised of six top members of the government, four of them military officers.)

Q: So, the Japanese leadership group addressed the Soviet invasion with extreme urgency — but didn’t do the same after the Hiroshima bomb?

A: Yes. When the Supreme War Council met on the morning of August 9, 1945, about six hours after the Soviet entrance into the Pacific war, it had been about 75 hours — or more than three days — since the atom attack on Hiroshima. Wrote Wilson, “What kind of crisis takes three days to unfold? The hallmark of a crisis is a sense of impending disaster and the overwhelming desire to take action now. How could Japan’s leaders have felt that Hiroshima touched off a crisis and yet not meet to talk about the problem for three days?”

Q: Why might the Soviet invasion have seemed so much more urgent than nuclear bombs?

A: Wrote Wilson, “It didn’t take a military genius to see that, while it might be possible to fight a decisive battle against one great power invading from one direction, it would not be possible to fight off two great powers attacking from two different directions. The Soviet invasion invalidated the military’s decisive battle strategy, as it invalidated the diplomatic strategy. At a single stroke, all of Japan’s options evaporated.”

Q: What was the decisive military strategy?

A: A deliberately suicidal plan called Operation Ketsu-Go — a defense of the Japanese home islands requiring every citizen to become a combatant. The plan’s “success” assumed an invasion from only one direction, however. And, as already noted, the diplomatic strategy had required the Soviets to act as peacemakers. Not only were those options suddenly gone, but the Soviet invasion had also effectively imposed a deadline on the Supreme War Council.

Q: How had the invasion imposed a deadline?

A: “The Soviet declaration of war,” Wilson wrote, “also changed the calculation of how much time was left for maneuver. Japanese intelligence was predicting that U.S. forces might not invade for months. Soviet forces, on the other hand, could be in Japan proper in as little as 10 days. The Soviet invasion made a decision on ending the war extremely time sensitive.”

Q: What happened at the Supreme War Council meeting?

A: “The Japanese government,” wrote Hasegawa, “still remained divided between those who advocated immediate surrender with only one condition, i.e., the preservation of the emperor system, and those who insisted on other conditions.”

Q: Was there any discussion of accepting an unconditional surrender — as Truman demanded?

A: No. Nor would there ever be.

Q: What happened next?

A: The Supreme War Council told Emperor Hirohito that they were divided on how to proceed.

Q: When did the members of the War Council learn about the Nagasaki atomic attack?

A: In the late afternoon of August 9, 1945, after the end of their meeting. So the second atomic bomb was not discussed.

[NOTE TO READER: In Chapter 19, the author promised that this chapter, Chapter 20, would conclude the series. But one more is considered necessary. There’s a duty to address the second atom bomb dropped on Nagasaki, the start of a nuclear cover-up campaign, and how a gloomy Robert Oppenheimer finally was having second thoughts about his “deadly toy.”]