After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 18 of 12, or more!)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: In Part 17, we returned to the long-running battle between the person ultimately in charge of delivering an atom bomb, General Leslie Groves, and the person who, single-handedly, pushed the U.S. to start researching the atom bomb, scientist Leó Szilárd. By June 1945, Szilárd had made himself the loudest voice questioning if the atom bomb should be dropped on Japan. For Groves, who had been keeping Szilárd under surveillance throughout World War II, questioning the necessity of using the bomb was all but treasonous. Here was the truth: Szilard was, in fact, loyal to the United States and Groves would fail to discover a mountain of super treasonous behavior. As mentioned in part 17 of this series, Stalin’s moles inside the Manhattan Project stole some 10,000 pages of technical data about the making of the bomb.]

Q: Really? 10,000 pages?

A: There was so much secret material that Lavrenti Beria, the paranoid psychopath running Stalin’s secret police, suspected that it was a trick by the British and Americans “designed,” as Dr. Matin Zuberi wrote, “to force the Soviet Union to spend huge resources and effort in a futile endeavor.” The fast-to-murder Beria told his underlings: “If it’s disinformation, I’ll throw you all into the [Lubyanka] cellar.” For most people who ended up in the “cellar,” a bullet to the back of the head was usually waiting.

Q: Who were the moles?

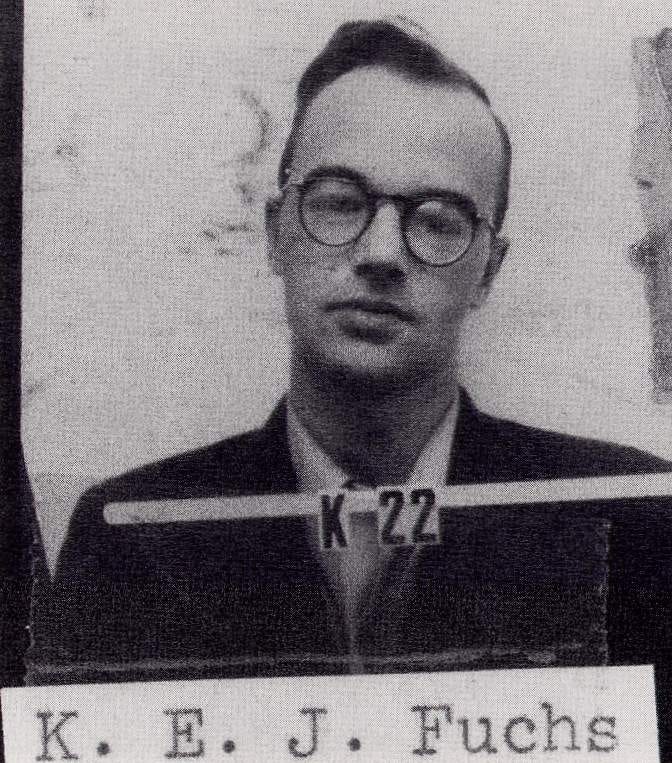

A: Klaus Fuchs may have been the most valuable player in Stalin’s all-star lineup of spies. He was the most accomplished physicist with the greatest access to the most sensitive and valuable information. (In Oppenheimer, Fuchs is played by Christopher Denham):

Q: Was there any evidence that Fuchs might have loyalty to the Soviet Union?

A: Yes. Let’s start with his family history. Fuchs was born and raised in Germany, the third of four children. Due to the leftist political views of his father, Emil, the family was taunted as “red foxes” — fuchs is the German word for fox. In 1933, Klaus’s father left the Lutheran Church to become a Quaker. During the Nazi political repression following the February 1933 Reichstag fire, three of Fuch’s family members were arrested and jailed: father Emil, for his pacifist activities; sister Elisabeth and brother Gerhard, for their Communist ties. Younger sister, Kristel, fled to the United States and married Robert Heinemann, a member of the U.S. Communist Party.

Q: Was Klaus Fuchs involved in Communist Party activity?

A: Yes. In 1930, Fuchs joined the student branch of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) at the University of Leipzig. At the same time, he also joined the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold, the paramilitary organization of the Social Democrats. In 1932, he was expelled from the SPD for supporting Communist Party leader Ernst Thalmann during Parliamentary elections. Fuchs then joined the German Communist Party (KPD). Fuchs and brother Gerhard became active speakers for the KPD and disrupted Nazi Party meetings. During a street battle with Nazis, Fuchs was beaten up and tossed in a waterway. In 1933, fearing he would be arrested or killed by the Nazis for his Communist activism, Fuchs fled Germany.

Q: Did Fuchs go to England after leaving Germany?

A: Not right away. His first stop was Paris, where he attended an anti-fascist conference funded by the Soviet Union and chaired by Henri Barbusse, a French Communist and Soviet propagandist. Ultimately, Fuchs came to England with the help of a Bristol family tied to communism.

Q: While Fuchs was living in England, were there indications he was still tied to communism?

A: Yes. Fuchs was working toward a doctoral in physics. In educational settings, he was described as shy and reserved. But Fuchs shed this guise at meetings of the Bristol branch of the Society for Cultural Relations with the Soviet Union. An eyewitness at one of the society’s events reported being surprised by an episode of “uninhibited behavior” from Fuchs. When members were performing dramatic readings of transcripts from Stalin’s new, controversial “purge” trials in Moscow, Fuchs played the role of lead prosecutor Andrei Vyshinsky. According to the eyewitness, Fuchs attacked the various faux defendants “with the cold venom that I would never have suspected from so quiet and retiring a young man.”

Q: When did Fuchs start sharing information with Soviet intelligence?

A: In 1941, Fuchs began informing Soviet military intelligence about a revolutionary weapon the British and the Americans were actively pursuing. A Soviet spy in London who worked with Fuchs provided this report: “The contact gave a short briefing on the principles behind the use of uranium for these aims. Just 1% of the energy of a 10-kilogram uranium bomb would produce an explosion equivalent to 1,000 tons of dynamite.”

Q: What other secrets did Fuchs share with the Soviets?

A: In 1943, in a cataclysmic security breach, Fuchs informed the Soviets about plutonium, the new synthetically-created substance to be used in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, known as “Fat Man.” Plutonium proved to be significantly more powerful than U-235, the uranium isotope used by the “Little Boy” device in the Hiroshima bombing. By 1944, Fuchs was on site at the Los Alamos Lab in New Mexico. He was one of 19 British nuclear scientists sent to the U.S. as part of collaborative agreement established by Churchill and Roosevelt. Fuch’s last act before leaving Los Alamos, in 1946, was to review every document in the Los Alamos archives, in particular those related to thermonuclear weapons design, therefore providing the Soviets with the latest work being done by Edward Teller, and others, on the vastly more destructive hydrogen bomb. (Below, “Fat Man” bomb that was copied by the Soviets, thanks to leaks from Fuchs):

Q: Was Fuchs caught?

A: Yes. But not until 1950, in Britain. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Q: Did Fuchs ever explain why he shared the atomic secrets?

A: “From the beginning of his involvement in bomb physics,” wrote Rudrangshu Mukherjee, “he did not want the bomb to be the monopoly of one power. This was the only reason he passed on information to the Soviet Union that, till the end of the war, was an ally of the U.S. and Britain but was deliberately kept out of the loop about a crucial development in the fight against Nazi Germany. Dick White, the head of both MI5 and MI6, noted that Fuchs’s motives were ‘relatively speaking, pure. Different from other spies, money was not the goal. He was a scientist who got cross at the Anglo-American ploy in withholding vital information from an ally fighting a common enemy.’’’

Q: Can an argument be made that Britain and the U.S. should have directly shared atomic bomb information with the Soviets, since they were a World War II ally?

Q: Yes — especially given the disproportionate level of sacrifice by the Red Army. “For obvious reasons,” wrote Timothy B. Lee, “American memories of World War II focus on episodes where the United States or our English-speaking allies played an important role. But it’s important to remember that the people of the Soviet Union bore a disproportionate share of the burden in fighting the German war machine. The Americans and British each suffered around 400,000 deaths of military personnel. France suffered 200,000. The number of Soviet deaths is disputed, but the Soviets lost at least 8.6 million soldiers and possibly as many as 13.8 million. In other words, around 90 percent of the Allies who died fighting the Nazis were Soviet.” (Below, stamp commemorating the 1943 Battle of Kursk, involving 8,000 German and Soviet tanks. Soviets casualties approached 700,000):

Q: Were there other important Soviet spies from Britain?

A: Yes – Allan Nunn May was another British scientist and Soviet mole. U.S. counterintelligence operatives may not have been aware that Nunn May had joined the British Communist Party in the 1930s. During the war, he was attached to the Manhattan Project as a physicist based in Canada, where the world’s most powerful research reactor had been built at Chalk River. Nunn May provided the Soviets with a clear overview of the functions of the key atomic sites: the Met Lab at the University of Chicago (where Szilárd, Fermi and many Nobel-Prize winners and top minds were clustered); Oak Ridge (site of isotope separation units to enrich uranium); Hanford (plutonium processing); and Los Alamos (bomb factory). Nunn May forwarded expert analysis of the July 16, 1945 Trinity atomic test shortly after it took place. He even shipped the Soviets a sample of enriched uranium, collected in a small glass tube. In 1946, he was convicted of espionage in Britain, sentenced to ten years hard labor, and released in 1952. (Below, Allen Nunn May):

Q: Were there more Brits leaking to the Soviets?

A: Yes. A trove of bomb secrets – and secrets about U.S. military and political activity – was funneled to the Soviets by three members of the Cambridge “Mag 5,” an infamous and incredibly productive ring of Soviet spies recruited at the super elite University of Cambridge in the 1930s.

Q: How did the Mag 5 members get access to atomic secrets?

A: Let’s start with John Cairncross. He had access to top-secret British War Cabinet documents while working as the private secretary to Lord Maurice Hankey, minister without portfolio who chaired the Science Advisory Committee. Cairncross subsequently gained two other posts dealing with highly-sensitive information: assigned to Bletchley Park, site of British codebreaking operations, and then to MI6, Britain’s CIA. Between 1941 and 1945, Cairncross supplied the Soviets with 5,832 documents, according to Russian archives. (He admitted to spying in 1951, but was not prosecuted. His identity as a “Mag 5” member wasn’t disclosed until 1990. Below, John Cairncross.)

Q: You indicated there there three in total. Two more to go. Who were the other “Mag 5” spies?

A: In 1943, another member of the “Mag 5,” Donald Maclean, was named to the Joint Anglo-American Combined Policy Committee, which was tasked with managing U.S., British and Canadian collaboration on the atomic bomb. With his perch on the Combined Policy Committee, Maclean reported to Moscow on the variety of areas he managed: economic warfare, civil aviation, military base negotiations, the acquisition of natural resources for wartime use, in particular sources of uranium for the Allied atom bomb project. In the middle of the war, Maclean was able to give the Soviets advance notice that General Leslie Groves was secretly trying to corner the world market of high-grade uranium ore. As a result, Stalin dispatched geologists to search the entire Soviet empire for sources of uranium. In 1944, Maclean managed to get himself sent to the United States. (Below, Donald Maclean):

Q: Did Maclean continue to be a productive Soviet asset in the U.S.?

A: Yes. He was 31 years old at the time and seen as a rising star in the British diplomatic corps. Maclean was also married to an American he’d met in Paris. In the U.S., the couple lived in Georgetown, the upscale locus of the capital’s power brokers. On July 4, 1945, Maclean informed the Soviets about the mid-July date of the Trinity test. As Richard Rhodes wrote in Dark Sun: “If Stalin needed evidence that the nations that called themselves his allies were colluding against him to deny him nuclear weapons while they built up their arsenal, Donald Maclean could supply it.”

Q: Who was the third member of the “Mag 5” to funnel top secret nuclear research to the Soviets?

A: Guy Burgess. During World War II, Burgess managed to work for the BBC, the Foreign Office, MI5 (Britain’s FBI), and MI6. Because of the flood of top-secret documents being produced by Burgess and Maclean, a new one-man section at Moscow Center was created to manage their files. The tedious and time-consuming work of translating the material from English to Russian perpetually lagged behind the rapid rate of incoming Allied secrets. Burgess’s spot inside British intelligence allowed him to give Stalin a heads up about British-U.S. plans for an intergovernmental military alliance between Europe and the United States, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). (Below, Guy Burgess):

Q: Were Maclean or Burgess caught?

A: No. In 1951, both Maclean and Burgess were exposed as moles by American VENONA codebreakers, who’d figured out how to read secret Soviet diplomatic traffic. But before these traitorous Brits could be apprehended, they were tipped off by Kim Philby, another “Mag 5” member who, conveniently, was the British liaison to the U.S. VENONA program. Warned in time by Cambridge-classmate Philby, Maclean and Burgess were able to bolt for the Soviet Union. (Philby eventually followed them, jumping on a Soviet freighter traveling from Beirut to Odessa, in 1963.)

Q: Were there American citizens who spied for the Soviets inside the Manhattan Project?

A: Yes. Perhaps the most famous is David Greenglass, who was tied to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Greenglass, Ethel’s brother, was a member of the Young Communist League when he was recruited to join a New York-based spy ring run by brother-in-law Julius. While a machinist at Los Alamos, he supplied the Soviets with sketches of his top-secret work on high-explosive lenses, a piece of the complicated hardware being developed to initiate a chain reaction inside the atomic bomb. Greenglass was arrested in 1950, pleaded guilty to committing espionage, and was sentenced to 15 years. A more significant U.S. spy at Los Alamos was never punished.

Q: Who was that?

A: Theodore Hall. Unlike Greenglass, who was more of a low-level worker bee at Los Alamos, Hall was a physics prodigy — a real-life version of the Big Bang’s Sheldon Cooper. He was recruited into spying by Harvard roommate Saville Sax, whose mother was a member of the Communist Party. At the age of 18, having already graduated from Harvard, Hall became the youngest scientist working at the Los Alamos Lab. Like Greenglass, he was assigned to the G (for gadgets) Division, but, unlike Greenglass, was assigned to the development of the implosion technique required to detonate the plutonium bomb — one of the most difficult challenges faced by the scientists. Hall was known to have supplied his Soviet handler with a list of all the key personnel at Los Alamos. He was investigated by the FBI in the early 1950s, but never charged.

Q: How was this mountain of nuclear intelligence put to use by the Soviets?

A: As Dr. Matin Zuberi wrote, “[Soviet atomic scientists] first confirmed through meticulous experiments and calculations the reliability of the rather detailed diagram and description of the first American bomb supplied by Klaus Fuchs and then decided to replicate it for the first Soviet explosion.” Zuberi also explained how Igor Kurchatov, the director of the Soviet atom bomb program, “used the intelligence reports first to evaluate the correctness of the data supplied and then to check the scientific results obtained by his colleagues.” (Below, Igor Kurchatov):

Q: Was Kurchatov the Robert Oppenheimer of the Soviet bomb program?

A; Yes. Like Oppenheimer, Kurchatov was a chain smoker — but may have worked even harder than his U.S. counterpart: reportedly 18 hours a day, seven days a week. His every wish was a command. The Soviet scientists working under him knew they were operating under a black-and-white premise: succeed or risk getting shot.

Q: Did the scientists supervised by Kurchatov know he was cheating?

A: No. He didn’t reveal that he was in possession of the “blueprints” of the American bomb. “Legends of Kurchatov’s scientific ‘intuition’ multiplied in the Russian nuclear establishment,” Zuberi wrote. “When his theoretical physicists reported a freshly calculated formula, he would silently open the safe containing intelligence material to compare the results. ‘No, it is not right,’ he would gently say. ‘You have to work more and come again.’”

Q: In 1945, the Soviets occupied the eastern portion of Germany. Did they capture world-class physicists and world-class scientific machinery to accelerate their bomb program?

A: Yes. Captured German manpower and machinery became an important additive. Nazi scientists were shipped to Black Sea research sites that were tasked with uranium processing and isotope separation. Pilfered German-made precision instruments — vaunted for their craftsmanship — permitted the Soviets to leap a technology gap. A Berlin factory used for producing pure uranium was dismantled and transported to the Soviet Union. The factory was rebuilt near Moscow, and renamed Elektrosal, becoming one of the first islands in the Soviet “atomic gulag.”

Q: Who should have alerted Harry Truman and Jimmy Byrnes (the U.S. bomb decision makers) to the possibility that Soviet spies and German acquisitions could help accelerate Stalin’s bomb program? Was it General Groves?

A: Yes. For example, Groves knew that Soviet espionage activity in the United States even targeted the most senior scientist on the project. In 1943, Robert Oppenheimer told Groves that he had rebuffed an inquiry about helping the Soviets that came from a friend and Berkeley colleague, left-wing literature professor Haakon Chevalier (played in Oppenheimer by English actor Jefferson Hall). Groves also went hunting for German physicists and German equipment. He oversaw the secret Operation Epsilon, which captured Werner Heisenberg and nine others attached to Nazi nuclear research. The German physicists were detained in an English country house – Farm Hall – for six months, starting on July 3, 1945. The Allies received an intimate picture of the German bomb program because, unbeknownst to the scientists, the house was bugged and all their conversations were being recorded.

Q: Was there anything else that General Groves missed regarding the Soviet atomic bomb program — and, by extension, the likelihood of the Soviets going nuclear?

A: Yes. Stalin had a virtually endless supply of slave labor. This allowed the necessary network of atomic facilities — research and production — to surface at lightning speed across the Soviet land mass.

Q: How did the Soviets mimic the giant industrial effort of the Manhattan Project?

A: In 1943, in the Silver Woods suburb of Moscow, the most powerful particle accelerator in Europe went into operation — despite massive battles with the Nazis still taking place on Soviet soil. Some 300 miles east of Moscow, a former monastery in Sarov became the Soviet version of Los Alamos. (After becoming part of the nuclear project, the complex disappeared from the map.) East of the Ural Mountains, a work force supplied by the gulags cut down a forest and dug a giant hole for Chelyabinsk-40, a production reactor built underground to shelter it from being bombed by American B-29s. In the short-grass steppe land of northeastern Kazakhstan, a nuclear testing site was established at Semipalatinsk.

Q: How much slave labor was used?

A: The Soviet Union used a workforce of about 700,000 on their atomic project, more than half of them prisoners. It was common to work the prisoners to death, which wasn’t a problem. Anytime more slave labor was needed, a new wave of terror, called a “vigilance campaign,” was authorized. People who had completed sentences and been released were rearrested, and people who were due to be released had their sentences extended indefinitely.

Q: In part 14 of this series, you wrote how, in 1944, Danish Nobel-Prize winning physicist Niels Bohr, given his vaunted expertise in nuclear science, had good reason to suspect that the Soviets were on their way to making their own bomb. Knowing this, he had begged Churchill and Roosevelt to speak openly with Stalin about the Manhattan Project. Bohr worried that hiding it from Stalin would ultimately induce him to start a nuclear arms race that could destroy humanity. But, given the information in this installment, it seems like Stalin always knew that Churchill and Roosevelt were hiding the bomb development from him?

A: Yes. Which made everything worse. As noted, the Soviets were an ally, and taking 90 percent of the casualties against the Nazis, and, as Stalin easily deduced, the only good reason to keep the bomb a secret from him was to allow his ostensible partners, Britain and U.S., to gain a massive and threatening military advantage over the Soviet Union. Moreover, as explained in chapter 17 of the series, Leó Szilárd was making the same points as Bohr a year later, in May 1945, but with Harry Truman’s top advisor, Jimmy Byrnes. Szilárd, also a groundbreaking nuclear physicist, told Byrnes that the Soviets would have a bomb within a few years and that hiding the U.S. nuclear program from Stalin would infuriate him and make the world a much less safer place. Like Bohr, Szilárd was ignored, as well. Also like Bohr, Szilárd was right.

[NOTE TO READER: In Chapter 19, Leó Szilárd gets lots of company from fellow Manhattan Project scientists in trying to keep the bomb from being used on Japanese civilians. Plus, at the final Big Three Summit of the war, Truman and Stalin appear to become enemies for life.]