After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 21 of 12 – and, at last, no more!)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: When we left you in Chapter 20, President Harry Truman and Jimmy Byrnes (Secretary of State and “co-President”) were not getting the payoff they wanted for birthing the nuclear age. The Hiroshima atomic attack had failed to meet their chief objectives: that is, it had failed to generate an immediate unconditional surrender by Japan and keep the Soviets on the sidelines of the Pacific war. Although the most destructive weapon ever made had been unleashed, the Japanese still weren’t budging, which, in turn, had provided Stalin with enough time to send 1.5 million Red Army troops into the battle. Meanwhile, on the island of Tinian, a second atom bomb was being loaded into a B-29 — to be dropped on Nagasaki, August 9, 1945.]

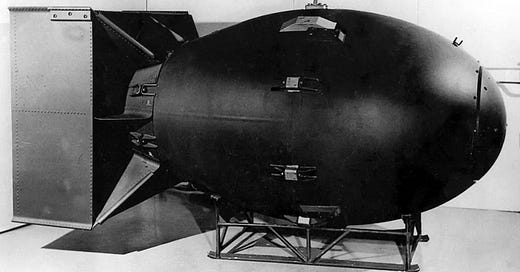

Q: What were the dimensions of the second atomic bomb?

A: Codenamed “Fat Man,” it was 10-feet-8 inches long, five feet in diameter, and weighed 10,265 pounds. Unlike the Hiroshima device, which used Uranium-235, the bomb that would be dropped on Nagasaki was powered by a more fissile — and therefore more powerful — daughter of uranium, plutonium, produced at nuclear reactors in Hanford, Washington. The method of detonation was also different for “Fat Man.” As the Dept. of Energy wrote, “Glenn Seaborg had warned that when plutonium-239 was irradiated for a length of time it was likely to pick up an additional neutron, transforming it into plutonium-240 and increasing the danger of pre-detonation.” (In 1941, while working at Cal, Seaborg had been the first to chemically identify plutonium, which became Element 94 on the Periodic Table — see chapter 9 in this series for more on that discovery. “Fat Man” is below):

Q: How did the Manhattan Project scientists seek to avoid pre-detonation of the plutonium bomb?

A: They invented an implosion-type triggering device. The core of sub-critical plutonium, weighing 13 pounds, was surrounded by a 5,300-pound layer of high-explosives. “The triggering system,” ChatGPT told the author, “involved a combination of detonators, explosive lenses, and a tamper that helped reflect neutrons back into the core, enhancing the efficiency of the explosion.” With this design, explosive force was directed inward, compressing the plutonium into a supercritical mass. Ultimately, the Nagasaki plutonium bomb produced a bigger blast than the Hiroshima uranium bomb, about 21 kilotons of TNT — or some five kilotons more than the Hiroshima device.

Q: What were the casualties and the damage from the Nagasaki bomb?

A: The pre-raid population of Nagasaki was 195,000. By one estimate, about 50 percent of residents died from the effects of the bomb — a death rate similar to Hiroshima’s. Ground zero in Nagasaki was the red-brick Urakami Roman Catholic Cathedral, one of the largest churches in Asia. Of 16,000 parishioners, it is estimated 10,000 were killed. (Below, destruction of Urakami Cathedral from bomb):

Q: Was Urakami Cathedral meant to be the target?

A: No. The Fat Man device missed its target — the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works — by nearly a mile, and, as a result, destroyed a mostly civilian district. The area within a few thousand feet of ground zero included Nagasaki Prison; Mitsubishi Hospital; Nagasaki Medical College; Chinzei High School; Shiroyama School; the Blind and Dumb School; Yamazato School; Nagasaki University Hospital; Mitsubishi Boys’ School; Nagasaki Tuberculosis Clinic; and the Keiho Boys High School. General Tom Farrell, who visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki a month after the attack, had this comment: “The effects of the Nagasaki explosion” were “more startling and more spectacular [than Hiroshima]. The destruction of the huge steel works by blast and fire and the destruction of the torpedo works by blast alone gives outstanding proof of the enormous amount of blast energy released. In all cases, the steel frames and buildings are pushed away from the point of detonation.” Of the city’s 50,000 homes, virtually all showed damage, with 11,494 blasted and burned.

Q: How did the Japanese react after the Nagasaki attack?

A: On the morning of August 9, 1945, just before the attack, a meeting of Japan’s Supreme War Council had addressed possible terms of surrender, but concluded in deadlock. The Council’s one point of unity was protecting Emperor Hirohito. Later on this same day, Tokyo learned about the second atom bomb and, at around midnight, Hirohito agreed to make an “unprecedented intervention” to solve the stalemate. On August 10, 1945, a radio broadcast from Tokyo announced that Japan was ready to accept terms of the Potsdam Declaration “with the understanding that said declaration does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a sovereign ruler.”

Q: So, even after two atomic bombs were dropped, Japan still insisted on a “conditional” surrender — keeping the Emperor?

A: Yes. (In Chapter 16 of this series, the author addresses the importance of the Emperor in more detail.)

Q: How did the U.S. react to Japan’s proposal of a “conditional” surrender?

A: At a White House meeting on August 10, 1945, Jimmy Byrnes continued to insist on nothing less than unconditional surrender. “I cannot understand,” said Byrnes, “why we should go further than we were willing to go at Potsdam, when we had no atomic bomb and Russia was not in the war.” He also warned that abandoning unconditional surrender could lead to "the crucifixion of the President" by the American public. But the meeting also included senior advisors who, for months, had been telling Truman that the “face saving” gesture of letting the Emperor stay was the best route to the fastest peace. They did so again. One of them, Secretary of Navy James Forrestal, arrived at a solution shrewd and simple. As Ronald Spector wrote, Forrestal suggested that “the United States should send a reply that reaffirmed the Potsdam demands while neither rejecting the Japanese offer nor discouraging hope that the emperor could remain.” Truman bought it.

Q: Why did Truman accept a conditional surrender?

A: To Truman’s thinking, the “Forrestal compromise” was close enough to “unconditional.” If the Japanese had to have their Emperor, the President wrote in his diary, “we’d tell ‘em how to keep him.” Byrnes took charge of telling the Japanese how they’d keep Hirohito, writing: “The authority of the Emperor shall be subject … to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces.” This would be the first time the U.S. had clarified the Emperor’s post-war role. (General Douglas MacArthur would be named the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Japan.)

Q: What happened next?

A: As historian Paul Ham wrote, “Byrnes drafted a compromise that read as an ultimatum … a little masterpiece of amenable diktat: it demanded an end to the Japanese military regime while promising the people self-government; it stripped Hirohito of his powers as warlord while re-crowning him ‘peacemaker.’” The U.S. expected Hirohito to command “all the Japanese military, navy and air authorities … to cease active operations and to surrender their arms.”

Q: What was the reaction in Japan?

A: Perhaps wishing a “conditional surrender” could somehow still be avoided, Byrnes waited until August 11, 1945 to send his “amenable diktat” to Tokyo, which, via neutral mediator Switzerland, arrived on August 12 in Japan. “At first,” wrote Ham, “America’s compromise had the perverse effect of deepening the factional divide between the three hardliners [on the Supreme War Council], who refused to believe it and pledged to fight on; and the three moderates, who pressed to accept it. Tokyo argued for three days. The Big Six vacillated over the meaning of Byrnes’ wording.”

Q: For example?

A: As Tsuyoshi Hasegawa explained, “Even those who initially favored peace questioned what the United States meant by saying that the Japanese emperor was ‘to be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers.’ The Japanese emperor was divine and not to be subjected to anything, the hard-liners insisted.”

Q: What took place during the three days that the Supreme War Council argued about accepting the U.S. counteroffer?

A: Truman decided not to drop a third atomic bomb, saying in a Cabinet meeting that the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was “too horrible,” especially the idea of killing “all those kids.” On August, 12, 1945, eight captured American fliers were beheaded and an American submarine and destroyer were sunk. On August 13, 1945, Truman ordered Hap Arnold to resume incendiary attacks on Japan. On August 14 and 15, more than 1,000 aircraft, with 12 million pounds of high explosives, attacked 30 targets. It is believed to be the largest air raid during the Pacific War. Half of Kumagaya was destroyed, a sixth of Isezaki.

Q: How was the stalemate in the Japanese Supreme War Council resolved?

A: “Helpless to decide what to do,” wrote Ham, “they appealed to Hirohito to make a second Divine Intervention. With his own life and dynasty now clearly intact, the Emperor recommended surrender.” On August 15, 1945, in taped remarks, Hirohito spoke to the Japanese nation by radio and accepted the altered Potsdam terms. It was the first time his voice had been heard by the Japanese public.

Q: Did Hirohito mention the bomb?

A: Yes. In the middle of the address, he said: “… the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

Q: Did Hirohito mention the Soviet invasion?

A: No.

Q: Why not?

A: “Attributing the end of the war to the atomic bomb served Japan’s interests in multiple ways,” wrote Ward Wilson. “The Bomb was the perfect excuse for having lost the war. No need to apportion blame; no court of enquiry need be held. Japan’s leaders were able to claim they had done their best … But attributing Japan’s defeat to the Bomb also served three other specific political purposes. First, it helped to preserve the legitimacy of the emperor. If the war was lost not because of mistakes but because of the enemy’s unexpected miracle weapon, then the institution of the emperor might continue to find support within Japan. Second, it appealed to international sympathy … Finally, saying that the Bomb won the war would please Japan’s American victors. The American occupation did not officially end in Japan until 1952, and during that time the United States had the power to change or remake Japanese society as they saw fit … If the Americans wanted to believe that the Bomb won the war, why disappoint them?”

Q: Are there notable Japanese figures who commented on the reason for surrender?

A: Japanese Navy Minister Mitsumasa Yonia reportedly told his admirals: “The atomic bomb and the Soviet entry into the war are, in a sense, God’s gifts — as they provided Japan with excuses to end a disastrous war.” Japanese historian Kazutoshi Hando said: “For Japan’s civilian population, the dropping of the atomic bombs was the last straw. For the Japanese Army, it was the Russian invasion of Manchuria.”

Q: What was the status of the Soviet offensive when Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender?

A: The Red Army was steamrolling Japanese forces in Manchuria and conducting successful amphibious operations on southern Sakhalin Island, in northern Korea, and on the Kurile Islands. Stalin had a hope the Soviets might even be able to occupy Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost main island, and, by doing so, have access to a huge population for slave labor.

Q: Did the Soviets stop fighting when Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender on August 15. 1945?

A: No. The Red Army remained in action until September 5, 1945 — which was three days after the ceremony for the “signing of the instrument of surrender” on the deck of the U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Stalin’s forces did not reach Hokkaido, but they did provide him with a massive amount of slave labor. About 600,000 captured Japanese soldiers were sent to gulags in Siberia and the Far East. The majority were eventually repatriated, though it took years. An estimated 60,000 never returned, dying in Soviet prison camps.

Q: Didn’t Stalin use slave labor for the Soviet version of the Manhattan Project?

A: Yes. For more, see Chapter 18 of this series.

Q: After Truman told Stalin about the bomb at the Potsdam Conference, on July 24, 1945, the Soviet dictator privately vowed to diplomat Andrei Gromyko that he would seek to speed up production of the atomic bomb. Did he do that?

A: Yes. In mid-August, Stalin met with Boris Vannikov, People’s Commissar of Munitions, and Igor Kurchatov, the director of the Soviet atomic bomb project. “A single demand of you comrades,” Stalin said. “Provide us with atomic weapons in the shortest possible time. You know that Hiroshima has shaken the whole world. The equilibrium has been destroyed. Provide the bomb —it will remove a great danger from us.”

Q: Unlike the remote, unpopulated location for the Trinity test, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks made it abundantly clear that the bomb had two ways of killing people — quickly, from the initial blast, and slowly, from exposure to radiation. How soon did the top figures in the Manhattan Project learn of the ongoing catastrophe in Japan from widespread fallout?

A: In Hiroshima in America, Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell report that, on August 24, 1945, General Groves received a telex from Los Alamos “indicating that project staff was ‘much concerned about Japanese broadcasts claiming murderous delayed radioactive effects at Hiroshima.’ Groves replied that he considered the reports a ‘hoax or propaganda.’” But at the very same time, one of America’s own nuclear scientists, Harry Daghlian, was experiencing the same exact fate as thousands of Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors — dying from acute radiation poisoning.

Q: Was Daghlian in Hiroshima or Nagasaki at the time of the bombing?

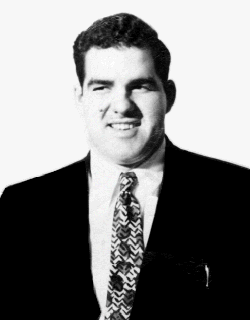

A: No. The 24-year-old Daghlian, an instructor from Purdue, was at Los Alamos working on the Manhattan Project. On August 21, 1945, in a remote part of the Los Alamos laboratory, Daghlian had accidentally dropped a tungsten brick on top of a sphere of plutonium that was already in the midst of a chain reaction. The dropped brick produced a flash of light, followed by a blue glow, indicating that the core had begun leaking radiation. Using his bare hands, Daghlian stopped the leak by disassembling the experiment. But, by doing so, he received an ultimately fatal dose of radiation. In the following days, Daghlian experienced nausea and vomiting, followed by blistering, dramatic weight loss, organ failure and delirium. He was comatose when he died on September 15, 1945 — just 25 days after exposure. The true cause of his death would not emerge for years. On September 21, 1945, the Associated Press reported that Daghlian had died “from burns in an industrial accident.” (Below, Harry Daghlian):

Q: Did any newspaper reporters ever witness Hiroshima or Nagasaki bomb survivors dying of exposure to radiation?

A: Yes. On September 2, 1945, after Australian war correspondent Wilfred Burchett took a train from Tokyo to Hiroshima, he’d write “the first independent account of the attack to appear anywhere in the world.” In a partially destroyed hospital, Burchett witnessed an appalling site: hundreds of people in the final stages of radiation disease. Three days later, Burchett’s account of his visit ran on the front page of the London Daily Express with this lead: “30 days after the first atomic bomb destroyed the city and shook the world, people are still dying, mysteriously and horribly — people who were uninjured in the cataclysm — from an unknown something which I can only describe as the atomic plague … I write these facts as dispassionately as I can in the hope that they will act as a warning to the world.”

Q: Was there any reaction to the story by the U.S. government?

A: Yes. General MacArthur withdrew Burchett’s press accreditation and announced his intention to expel the Australian reporter from occupied Japan. Burchett’s camera was confiscated. Friends in the U.S. Navy were able to have the expulsion order revoked, but Burchett’s publisher asked him to leave the country. In 1980, Burchett would say: “Hiroshima had a profound effect upon me. Still does. My first reaction was personal relief that the bomb had ended the war … My anger with the U.S. was not, at first, that they had used that weapon — although that anger came later. Once I got to Hiroshima, my feeling was that for the first time a weapon of mass destruction of civilians had been used. Was it justified? Could anything justify the extermination of civilians on such a scale? But the real anger was generated when the U.S. military tried to cover up the effects of atomic radiation on civilians — and tried to shut me up. My emotional and intellectual response to Hiroshima was that the question of the social responsibility of a journalist was posed with greater urgency than ever.”

Q: Did any American reporter witness the effects of radiation from the atom bombs?

A: Yes. On September 6, George Weller of The Chicago Daily News became the first American reporter to visit Nagasaki after the atomic bombing. The story he wrote described the same lingering medical effects, a mysterious "atomic illness" that was killing patients who outwardly appeared to have escaped the bomb's impact. However, unlike Burchett, Weller sent his piece directly to General MacArthur’s Tokyo headquarters for clearance, where it was spiked. Weller's articles were not made available until 2006.

Q: In Chapter 19, you noted that, on September 11, 1945, General Groves was leading a tour of reporters at “ground zero” of the Trinity test site, in New Mexico. He was doing this to challenge the reports about the danger of radiation. Did Groves get the press he wanted?

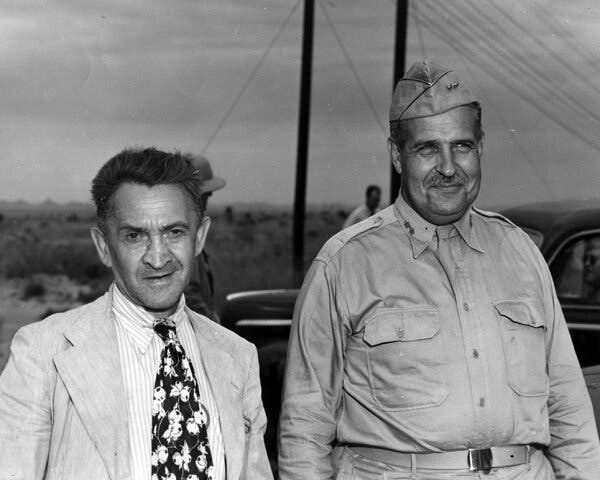

A: The country’s most influential paper complied. One of the 30 reporters selected to make the visit was the Pulitzer-Prize-winning science reporter of the The New York Times, William Laurence. The next day, September 12, 1945, the front page of The Times included a story written by Laurence with this headline: U.S. ATOM BOMB SITE BELIES TOKYO TALES: TESTS ON NEW MEXICO RANGE CONFIRM THAT BLAST, AND NOT RADIATION, TOOK TOLL. (Below left, William Laurence, with General Groves at Trinity site in September 1945. Photo courtesy of Atomic Heritage Foundation):

Q: Was there any basis for minimizing radioactive fallout?

A: No. Worse, Laurence knew it was a lie.

Q: How did Laurence know the story was a lie?

A: As Amy Goodman wrote, “Laurence had observed the [Trinity] test on July 16, 1945, and he withheld what he knew about radioactive fallout across the southwestern desert that poisoned local residents and livestock. He kept mum about the spiking Geiger counters all around the test site.” Moreover, the story fit a pattern of unethical behavior.

Q: What else was unethical?

A: In addition to printing lies about a life-and-death issue that he knew were lies, Laurence was also, as Goodman wrote, “on the payroll of the War Department. In March 1945, General Leslie Groves had held a secret meeting at The New York Times with Laurence to offer him a job writing press releases for the Manhattan Project.” The Times leadership not only approved of the arrangement, but in a time of intense patriotic fervor, felt honored to have their own reporter selected. Further, as Goodman noted, “Laurence helped write statements on the bomb for President Truman and Secretary of War Henry Stimson.”

Q: Did Laurence continue to mislead the public about radiation damage?

A: Yup. The day after lying to Times readers about radioactive fallout from the New Mexico test, Laurence let the deputy general under Groves lie to Times readers about the radioactive fallout in Hiroshima. On September 13, 1945, under the headline, NO RADIOACTIVITY IN HIROSHIMA RUIN, Laurence wrote: “Brig. Gen. T. F. Farrell … denied categorically that [the bomb] produced a dangerous, lingering radioactivity in the ruins of the town.”

Q: Should Laurence have strongly suspected that Farrell was lying?

A: Yes. Laurence had witnessed the Nagasaki blast from an observation plane. As Mark Wolverton wrote, Laurence was “slated for a later visit [to Nagasaki] to get an on-the-ground view for himself, but was instead literally pulled off the airplane minutes before its departure and ordered back to the States and The New York Times.”

Q: How do we know that General Farrell was also lying?

A: Farrell had been sent to Japan by Leslie Groves with “unofficial orders” to corroborate the thesis that there was no radioactivity from the bomb. On September 10, 1945, after touring hospitals in Hiroshima, he confirmed the opposite. In a top-secret cable, Farrell observed: “Summaries of Japanese reports previously sent are essentially correct, as to clinical effects from single gamma radiation dose.” General Farrell next traveled to Nagasaki and, on September 14, 1945, wrote another cable to Groves: “Japanese officials report that anyone who entered the blast area from outside after the explosion has become sick.”

Q: Did any other reporters in Japan provide true accounts about the thousands dying of radiation sickness in Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

A: Not for many months. On September 19, 1945, General MacArthur imposed sweeping censorship rules on the flow of information within Japan. The guidelines of “journalistic ethics” included this restriction: “Nothing shall be printed which might, directly or by inference, disturb the public tranquility.” In Fallout, Lesley M.M. Blume would call the atomic-related censorship campaign “one of the deadliest and most consequential government cover-ups of modern times.” The censorship rules were also applied to Japanese scientists.

Q: Scientists were censored?

A: Yes. “Japanese scientists studying the effects of the atomic bomb also had to submit their papers to the censorship board for review,” wrote Lifton and Michell. The papers would be held indefinitely, discouraging vital research. Lifton and Mitchell also noted that: “Dr. [Masao] Tsuzuki, the radiation authority, called it ‘unforgivable’ to restrict scientific investigation and publications while people were dying from a mysterious new disease … Censorship would not end until 1949, and scientific papers could not be freely published for two years after that. During this period, the atomic bomb was virtually a forbidden subject in Japan.”

Q: In 1945, was there any film released showing the after effects of the bombs?

A: Filming was also banned in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but one exception was allowed. Lieutenant Daniel McGovern of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey convinced his superiors that footage of the targeted cities would be “irreplaceable” and of “inestimable value” because the conditions “will not be duplicated until another atomic bomb is released under combat conditions.” Working with Japanese filmmakers, McGovern completed a nearly three-hour documentary entitled The Effects of the Atomic Bombs Against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After completion, the film was immediately declared Top Secret and 125,000 feet of raw footage went missing. (When the documentary was finally declassified, in 1967, the U.S. government couldn’t produce a copy. However, McGovern had secretly kept prints of the finished film — as did one of his fellow filmmakers in Japan.)

Q: Did Robert Oppenheimer ever see film of the devastation from the bomb?

A: Yes. A few days after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Oppenheimer gathered Los Alamos scientists to screen aerial footage of what was left of the city. Reportedly, no one spoke. Hans Bethe would say, “We were really horrified.” Oppenheimer asked if “the living might envy the dead.”

Q: After the war, did Oppenheimer remain in charge of the Los Alamos Lab?

A: No. On October 16. 1945, Oppenheimer resigned as lab director. A farewell ceremony was held in his honor at Los Alamos. “If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of nations preparing for war,” he said at the occasion, “then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and of Hiroshima.”

Q: In Nolan’s Oppenheimer, we see a meeting at the White House between Robert Oppenheimer and Harry Truman. Did that happen?

A: Yes. Nine days after resigning from the Los Alamos lab, on October 24, 1945, Oppenheimer was in the Oval Office meeting Harry Truman for the first time. Truman asked him when the Soviets would develop an atomic bomb. When Oppenheimer said he didn’t know, Truman provided his own answer, barking: “Never!” At another point, Oppenheimer said to Truman, “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” Truman responded angrily, “The blood is on my hands. Don’t you worry about it.” Truman later called Oppenheimer a “cry-baby scientist” and told Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson: “I don’t want to see that son of a bitch in this office ever again.”

Q: While he was in Washington, did Oppenheimer share his guilt about the bomb with anyone else?

A: Yes. Oppenheimer also met with Henry Wallace, at the time Truman’s Secretary of Commerce. “I never saw a man in such an extremely nervous state as Oppenheimer,” Wallace wrote in his diary. “He seemed to feel that the destruction of the entire human race was imminent … He had been in charge of the scientists in New Mexico and says that the heart has completely gone out of them there; that all they think about now are the social and economic implications of the bomb and that they are no longer doing anything worthwhile on the scientific level … He says that Secretary Byrnes’s attitude on the bomb has been very bad … He thinks the mishandling of the situation at Potsdam has prepared the way for the eventual slaughter of tens of millions or perhaps hundreds of millions of innocent people.”

Q: Any final words?

A: Yes. The author will go back to his recommendation from Chapter 1 of this series: If you haven’t seen Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, take the time to do so. In addition, the author would also like to reprise the words of the New Republic’s David Klion: “Oppenheimer turns out to be uncomfortably timely. At no point since the end of the Cold War has nuclear war felt more plausible, as the daily clashes between a nuclear-armed Russia and a NATO-backed Ukraine remind us. Beyond literal nuclear warfare, we are faced with a range of existential dangers — pandemics, climate change, and perhaps artificial intelligence — that will be managed, or mismanaged, by small teams of scientific experts working in secret with little democratic accountability … Oppenheimer’s dark prophecy may yet be fulfilled.”