After seeing Nolan's 'Oppenheimer,' do you have questions?

Everything you wanted to know about the making of the atomic bomb – with guaranteed surprises and some really scary stuff! (Part 17 of 12, or more!)

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: In Part 16, we reviewed the World War II endgames for Japan, the Soviet Union and the United States. In short, all three countries were in a wait-and-see mode. The Japanese were waiting to see if they could arrange a surrender that protected their Emperor. Stalin was waiting to see if he could open a new front in the Pacific before the Japanese capitulated. Harry Truman, and “co-President” Jimmy Byrnes, were waiting to see if the atom bomb worked, because, if this secret weapon made a big enough bang, they were hoping it would compel an immediate unconditional surrender from Japan … and keep the Soviets out of the war in the Pacific … and frighten Stalin enough to make him slow his push to rule all of Eastern Europe behind an Iron Curtain.]

Q: If we have learned one thing from this series, it is that Leó Szilárd is irrepressible. Did Szilárd attempt to meet with the new President?

A: Yes. When Missourian Truman moved into the Oval Office, on April 13, 1945, Szilárd went looking for a Manhattan Project scientist from Missouri and found Albert Cahn, a Kansas City mathematician who provided a path to reach the new President. Not surprisingly, this overwhelmed new President tasked with ending a world war was a little busy and it took weeks to get a White House appointment, which was scheduled for May 25, 1945.

Q: What happened when Szilárd went to the White House?

A: He carried Einstein’s March 25, 1945 letter of introduction with him (find more details in part 15 of the series; the letter had initially been written for Roosevelt). Szilárd had also brought the memorandum he wrote to accompany the letter to FDR. Matthew Connelly, Truman’s appointment secretary, read the documents and said to Szilárd, “I see now this is a serious matter. At first, I was a little suspicious because this appointment came through Kansas City [headquarters for the corrupt Pendergast machine that, in 1934, boosted Truman into national office]. The president thought that your concern would be about this matter, and he asked me to make an appointment for you with James Byrnes, if you are willing to go down to see him in Spartanburg, South Carolina.”

Q: What happened next?

A: On May 27, 1945, Szilárd boarded the overnight train to South Carolina. So did an undercover agent tracking Szilárd’s every movement, as demanded by General Leslie Groves.

Q: Did Szilárd wonder why he was going to see Byrnes?

A: Yes. As far as the press and the public understood, Byrnes had no government role after resigning from his senior White House position following the death of Franklin Roosevelt, on April 12, 1945. (Below, recent photos of Converse Heights neighborhood in Spartanburg, S.C.; on the right is the home where Byrnes and Szilárd would have their May 1945 meeting):

Q: Can you set the scene of the meeting between Byrnes and Szilárd?

A: Yes. Byrnes was staying in the Spartanburg neighborhood of Converse Heights, a community of modest brick Colonials, enhanced with shutters and columns, fronted by tidy lawns. When the native South Carolinian opened the door on the evening of May 28, 1945, the visiting scientist in front of him was short and stout, five-foot-six inches, with thick, wavy hair, starting to recede, and a round face highlighted by warm brown eyes, advertising intensity and intellect. Byrnes was about the same height, but decidedly thinner, wiry, his eyes small and deeply set, his nose narrow and elongated, hair gray, sparse, but smartly trimmed.

Q: Did these men have much in common?

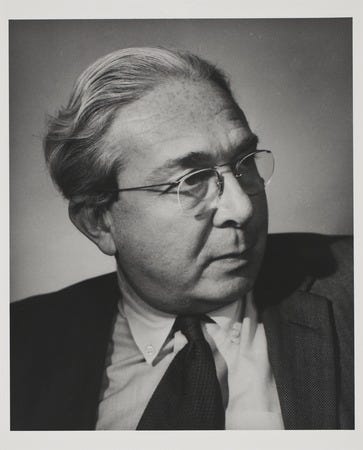

A: No. The origins and mentalities of Jimmy Byrnes and Leó Szilárd were studies in opposition. Szilárd, age 47 at the time, was a Jewish, Hungarian-born peripatetic refugee, who had recently made it habit to keep a packed suitcase on stand-by anywhere he landed. In Germany, Szilárd had literally been taught quantum physics by Einstein, transitioned into concocting inventions with Einstein, and, by his early 30s, was one of the greatest scientific minds of his time. The 63-year-old Byrnes, in his fourth decade of continuous public service, was a classic American success story. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, to a working single mother, he had left school at age 14 to take a job as a runner in a law office, where he cleaned and performed errands. He next learned shorthand to become a court reporter, during which time he taught himself the law by spending nights in the law library of the firm that had hired him as a teenager. David Robertson’s biography of Byrnes would be titled: “Sly and Able.” Truman, in his diary, would call Byrnes a “country politician, keen, conniving, suspicious,” but, Truman believed, also “honest.” (Below, Szilárd (left) and Byrnes):

Q: Did Szilárd give Byrnes the letter of introduction from Einstein?

A: Yes, and his memo. The letter from Einstein recommending Szilárd should have carried more weight. It didn’t because Jimmy Byrnes had already heard a decidedly negative view of Leó Szilárd from General Leslie Groves.

Q: What were some of the key points in Szilárd’s memo?

A: There were four.

Q: Number 1?

A: Szilárd argued that the pretext for creating an atomic weapon had vanished: “Until recently we have had to fear that the United States might be attacked by atomic bombs during this war and that her only defense might lie in a counterattack by the same means … With the defeat of Germany, this danger is averted.”

Q: Number 2?

A: Szilárd asked Byrnes to envision a future in which the United States, after detonating the first atomic bomb, would obtain only a short-lived monopoly on nuclear weapons: “Perhaps the greatest immediate danger which faces us is the probability that our ‘demonstration’ of atomic bombs will precipitate a race in the production of these devices between the United States and Russia and that if we continue to pursue the present course, our initial advantage may be lost very quickly in such a race.”

Q: Number 3?

A: Not only would Russia [a.k.a. the Soviet Union] soon be able to build an atomic weapon, Szilárd explained, but once the Soviets did so, they’d gain a clear advantage because the United States had many more large, densely-populated urban areas than the Soviet Union. If Stalin possessed just two or three dozen nukes, it would pose a mortal threat to every major American city. In the memo, Szilárd wrote: “A single bomb of this type … may be expected to destroy an area of ten square miles. Under the conditions expected to prevail six years from now, most of our major cities might be completely destroyed in one single attack and their populations might perish.”

Q: Number 4?

A: Szilárd politely demanded a seat at the table, seeking to institutionalize what H.G. Wells had imagined: an open conspiracy of scientists who acted as equals with the political class: “The decisions ought to be based not on the present evidence relating to atomic bombs, but rather on the situation which can be expected to confront us in this respect a few years from now … This situation can be evaluated only by men who have first-hand knowledge of the facts involved … by the small group of scientists who are actively engaged in this work.” (A Scientific Panel had just been formed to advise the Interim Committee on the bomb, which was essentially ruled by Byrnes. The scientists selected were Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, Enrico Fermi and Arthur Compton. At that point, there was a less-than-zero chance of Szilárd being picked for such a role. However, being an advisor wasn’t what Szilárd was suggesting to Byrnes. He really wanted decision-making power.)

Q: How did Byrnes respond in this South Carolina suburban summit with Szilárd?

A: Byrnes, who had been told that the Soviet Union wasn’t likely to produce an atomic weapon for many years, didn’t see an arms race on the near horizon. Szilárd pushed back. SZILÁRD: “I think Russia will be become a nuclear power soon, especially if we demonstrate the power of the bomb and use it against Japan.” BYRNES: “General Groves tells me there is no uranium in Russia.” SZILÁRD: “It is very unlikely that within the vast expanse of Russia there is no low-grade uranium ores.”

Q: Was Szilárd correct?

A: Yes. General Groves – who was not a geologist, nor any kind of scientist – had badly misinformed Byrnes about Soviet access to uranium. As of 1910, the Russians had already located uranium ore inside their borders. When the Soviet Union began its nuclear research, in 1940, a wider search of the country was conducted, and additional locations discovered. Further, the Soviets gained access to significant uranium deposits when they occupied Czechoslovakia, in 1944, where 12,000 World War II prisoners were put to work in the mines. More uranium was sourced after the Soviets occupied North Korea, in August 1945.

Q: Did General Groves think the Soviets would ever be able to build a nuclear weapon?

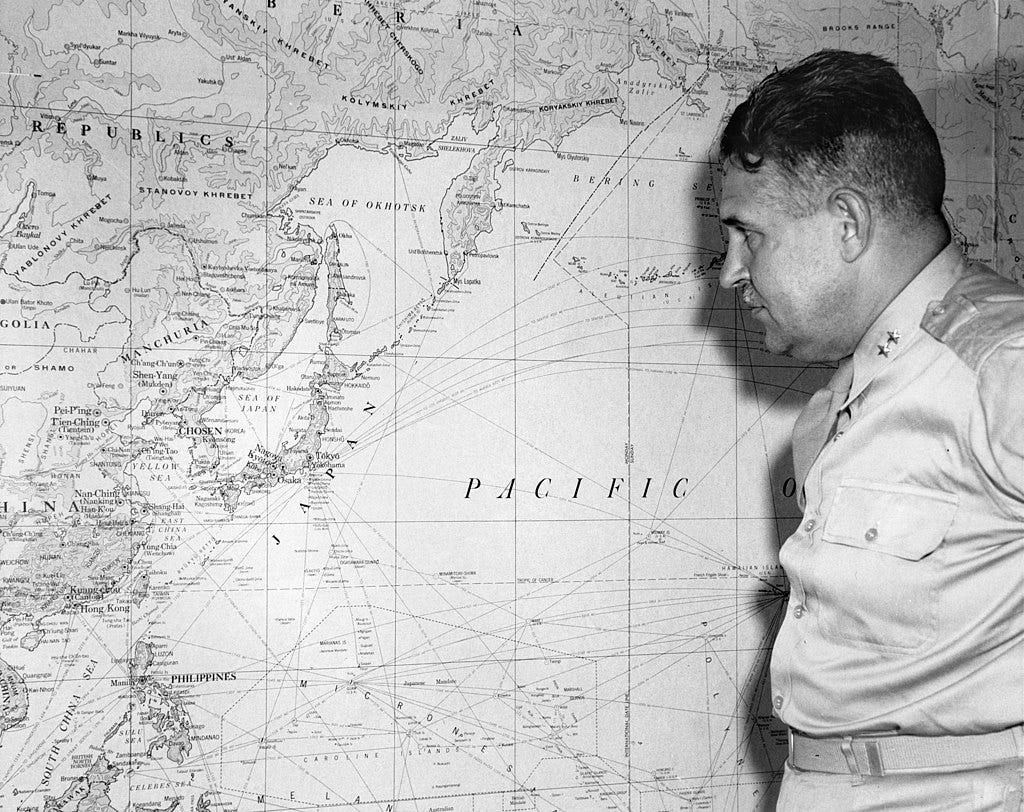

A: Yes, but he thought it would take 20 years. Which was wildly wrong. In 1946, just a year after the end of World War II, the Soviets created a chain reaction in an experimental reactor, just like the one built at the University of Chicago by Enrico Fermi and Leó Szilárd. In 1948, a year before the Soviets detonated their first atomic bomb, Groves would compound his ignorance, writing this profoundly chauvinistic and inaccurate assessment in the Saturday Evening Post: “The Soviet Union simply does not have enough precision industry, technical skill, or scientific numerical strength to come even close to duplicating the magnificent achievement of American industries.” (Below, Groves with map of Japan):

Q: What else did Byrnes and Szilárd discuss?

A: Byrnes admitted that he expected the bomb to have the added value of intimidating Stalin. BYRNES: “I’m concerned about Russia’s postwar behavior. Russian troops have moved into Hungary and Romania. I believe it will be very difficult to persuade Russia to withdraw her troops from these countries, and Russia might be more manageable if impressed by American military might.” SZILÁRD: “I share your concern about Russia throwing her weight around in the postwar period, but I disagree that rattling the bomb might make Russia more manageable. I fail to see how sitting on a stockpile of bombs, which we could not possibly use, will have this effect. I think it’s conceivable that doing so will even have the opposite effect.”

Q: Did Szilárd prove to be correct about Stalin’s reaction to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic attacks?

A: Yes. As Szilárd predicted, Stalin didn’t became more submissive. Rather, he was enraged and made production of an atomic bomb his number one priority. Stalin would also react badly to the bullying posture Byrnes adopted after the bombs were used on Japan. “A-bomb blackmail is American policy,” Stalin would say. “It is obvious that we cannot achieve anything serious if we begin to give in to intimidation or portray uncertainty.”

Q: Did Byrnes seem to give serious consideration to anything Szilárd told him on that May night in Spartanburg?

A: No. Byrnes actually appealed to Szilárd’s roots to justify “A-bomb blackmail as American policy.” BYRNES: “Well you come from Hungary – you would not want Russia to stay in Hungary indefinitely.” SZILÁRD: “I’m more concerned at this point that by demonstrating the bomb and using it in the war against Japan, we might start an atomic arms race between America and Russia, which might end with the destruction of both countries. I’m not disposed at this point to worry about what would happen to Hungary.”

Q: So can we blame Jimmy Byrnes for playing a big role in seeding a nuclear arms race with the Soviets?

A: Yes. As Szilárd predicted, an uninhibited nuclear arms race did begin. The United States and the Soviet Union together manufactured more than 100,000 nuclear devices during the Cold War. During that nearly 50-year-period, when the U.S. and Soviet defense establishments maintained a 24-7, hair-trigger alert, nuclear mistakes and accidents brought the world to the very brink of extinction multiple times. The exact number of times we experienced such a “near-miss” during the Cold War is likely never to be known.

Q: After Szilárd left the Byrnes residence, what was his judgement about the meeting?

A: Szilárd suspected he had completely failed to slow the march toward a future piled high with nuclear weapons. He would later say he was rarely as depressed as when he left the house in Spartanburg and walked toward the train station: “I thought to myself how much better off the world might be had I been born in America and become influential in American politics, and had Byrnes been born in Hungary and studied physics. In all probability, there would have been no atom bomb, and no danger of an arms race between America and Russia.” (Below, recent photo of the train station in Spartanburg, South Carolina):

Q: Did Byrnes ever comment on the meeting with Szilárd?

A: Yes. Byrnes later said, “Szilárd complained that he and some of his associates did not know enough abut the policy of the government with regard to the use of the bomb. He felt that scientists, including himself, should discuss the matter with the Cabinet, which I do not feel desirable. His general demeanor and his desire to participate in policy made an unfavorable impression on me.”

Q: Did Szilárd give up?

A: Of course not. After taking the train back to Washington D.C., Szilárd was “eager to influence the Interim Committee,” wrote William Lanouette, and “audaciously telephoned General Groves’s office in the New War Building on May 30 to arrange a meeting there with Oppenheimer for later that morning.” As a member of the Science Panel, Oppenheimer had been invited to attend the May 31, 1945 meeting of the Interim Committee.

Q: What happened when Oppenheimer and Szilárd met?

A: SZILÁRD: “It would be a serious mistake to use the bomb against Japanese cities.” OPPENHEIMER: “The atom bomb is shit.” SZILÁRD: “What do mean by that?” OPPENHEIMER: “Well, this is a weapon that has no military significance. It will make a big bang — a very big bang — but it is not a weapon which is useful in war.” The conversation turned to alerting Stalin.

Q: Did Oppenheimer think Stalin should be alerted?

A: Yes. But, unlike Oppenheimer, Szilárd thought that merely telling Stalin wasn’t sufficient. Like Niels Bohr, Szilárd believed the future peril of an arms race required a much deeper level of cooperation with the Soviets — and other nations — on how to safely manage atomic power. OPPENHEIMER: “Well, don’t you think if we tell the Russians what we intend to do and then we use the bomb in Japan, the Russians will understand it?” SZILÁRD (sarcastically, recalling how Byrnes wanted to terrorize Stalin with the bomb): “They’ll understand it only too well.”

Q: Should we assume Szilárd kept up his campaign to prevent U.S. leadership from blindly stumbling into a nuclear arms race?

A: Yes. He did. As Richard Rhodes reported, Szilárd “traveled on to New York after talking to Oppenheimer and … looked up Boris Pregel, the Russian-born French metals speculator and bon vivant who had helped out in the early Columbia days and whose mine on Great Bear Lake supplied the Manhattan Project with uranium ore.” (Szilárd began working with Pregel in 1939, a topic covered in part four of this series.) Reportedly, Szilárd and Pregel got into a conversation about how a top U.S. Army officer (meaning General Leslie Groves) was misinforming Jimmy Byrnes about Russia’s sources of uranium ore.

Q: Is it logical to assume that Groves was aware of this Szilárd-Pregel conversation from his intelligence operatives?

A: Groves was aware. At the May 31, 1945 meeting of the Interim Committee — which concluded with the judgement that the bomb should be used as soon as possible against Japan, and without informing Stalin ahead of time — Groves felt it necessary to digress and tell the room that “the program has been plagued since its inception by the presence of certain scientists of doubtful discretion and uncertain loyalty.” The comment was a reference to Szilárd. Groves also advocated “a general weeding out of personnel no longer needed” after the bomb became public, which was also a reference to Szilárd. On June 1, 1945, Groves wrote a top secret memo with his latest thoughts on the nettlesome, free-thinking Hungarian.

Q: What did the top-secret memo say?

A: Groves wrote, “Szilard is a physicist who has worked on the project almost since its inception. He considers himself largely responsible for the initiation of the project, although he really had little to do with it. When the Army took over the project, an intensive investigation was made of Szilard because of his background and uncooperative attitude on security matters. This investigation and all experience in dealing with him has developed that he is untrustworthy and uncooperative, that he will not fulfill his legal obligations, and that he appears to have no loyalty to anything or anyone other than himself. He was retained on the project at a large salary solely for security reasons.”

Q: Did Groves ever catch Szilárd doing anything even remotely treasonous?

A: No. As previously noted in this series, Groves confused dissent with treason. Meanwhile, as the general’s counterintelligence agents were crossing America to keep a tail on Szilárd, a legion of Soviet moles inside the Manhattan Project were going undiscovered. In all, some 10,000 pages of stolen technical data about the U.S. atom bomb would be forwarded to Soviet physicists, including experiments and designs related to every aspect of the bomb’s development: the physiology of uranium, isotope separation, gaseous diffusion, centrifuges, the construction of reactors, and drawings of the custom-made machinery used to detonate of the bomb. This espionage home run was another reason why the Soviets were going to rapidly make their own bomb.

[NOTE TO READER: Your next question might be: Who were the moles? Next, in part 18, you’ll find out!]